Economic Weekly 49/2025, December 12, 2025

Published: 12/12/2025

Table of contents

The EU Seeks Ways to Finance Ukraine Using Frozen Russian Reserves

EUR 210 bn value of frozen Russian assets located in EU Member States

EUR 185 bn frozen Russian assets held in Belgium’s Euroclear

EUR 1.7 bn Belgium’s 2024 tax revenue from interest on frozen Russian assets

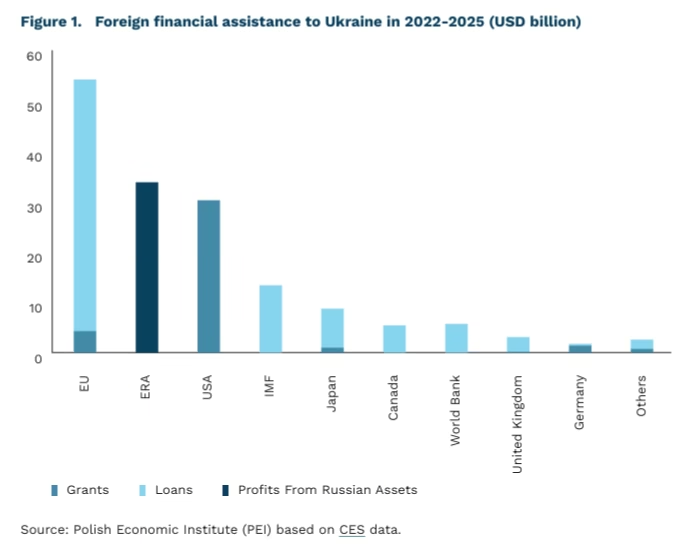

The European Commission has proposed a credit mechanism that would allow EU financial institutions holding Russian reserves frozen under sanctions to lend these funds and transfer them to Ukraine. The non-interest-bearing reparations loan is to total a maximum of EUR 210 billion, of which EUR 90 billion could be used within the next two years. According to the Commission’s proposal, Ukraine would repay the loan only once it receives financial reparations from Russia for war-related destruction. The loan would also be guaranteed by EU Member States in proportion to their national income, ensuring security in the event that repayment becomes unexpectedly necessary before the Kremlin pays compensation to Ukraine. EU leaders are expected to take a decision on Ukraine financing at the summit on 18 December of this year.

Belgium has been the most vocal opponent of the Commission’s proposal, since the majority of frozen assets is held in the Belgian clearing house Euroclear (approx. EUR 185 billion). Belgian authorities underline both legal and financial risks and demand that these risks be more evenly shared by the remaining EU Member States. Belgium also benefits financially from holding frozen Russian reserves, due to taxes which amounted to EUR 1.7 billion in 2024. It also emphasises the risk that entities from third countries may turn away from the EU as a desirable location for asset placement. However, available data suggest that existing sanctions on Russia have not led to a broader shift away from Western currencies. The most serious consequences may stem from potential retaliatory steps by the Kremlin, including the seizure of European assets in Russia (a concern voiced, among others, by Euroclear). Russia could also file claims before international arbitration tribunals against Belgium and European banks holding the frozen assets, on the basis of bilateral investment treaties.

The EU faces the need to secure new sources of funding for Ukraine in light of the phase-out of US financial support. Ukraine, for its part, is confronted with a budget deficit exceeding EUR 70 billion in 2026, and without continued support it will be forced to introduce major budget cuts as early as spring. A significant proportion of foreign assistance is already based on the mechanism for transferring profits generated by frozen Russian assets (the ERA mechanism). In the first eleven months of 2025, foreign assistance covered 57% of Ukraine’s budgetary needs, compared with 73% in 2024. This means that Ukraine’s tax revenues are fully directed towards financing the war effort, while foreign assistance covers all remaining budget expenditures. After Donald Trump took office, US financial support for Ukraine expired, while the EU’s share in assistance increased. Another motivation for expediting the Commission’s work may be the fact that a proposal unfavourable to the EU regarding the use of Russian reserves appeared among the 28 points on war termination reportedly prepared by President Trump’s special envoy Steve Witkoff and the Kremlin’s representative Kirill Dmitriev. According to that proposal, part of the funds would be allocated to Ukraine’s reconstruction projects, while the remainder would go to US-Russian joint ventures, with the United States receiving a share of the profits.

Jan Strzelecki, Marcin Klucznik

Germany on the Brink – Minimal Growth, Industrial Weakness and Export Uncertainty

0.2% projected GDP growth for Germany in 2025

1.8% increase in industrial production value in October 2025

-1.4% forecast change in Germany’s net exports in 2025

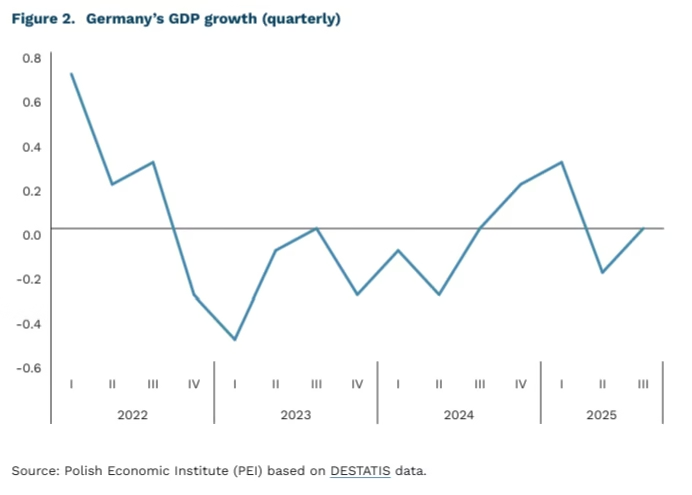

The pace of Germany’s GDP growth remains exceptionally weak. The outlook for 2025 is far from optimistic: the IMF forecasts German GDP growth of 0.2% after two years of stagnation. The current recovery is minimal and driven mainly by domestic demand, which is expected to increase by 1.7% y/y. The key pillars of the German economy – industry and exports – still show no lasting improvement. Short-term dynamics also remain unchanged: GDP fell by 0.3% in Q2, and no growth was recorded in Q3. The only positive development is moderate inflation, which stood at 2.3% y/y in November.

Industrial production presents a mixed picture. In October, the value of industrial output increased by 1.8% m/m, following a month-on-month rise of 1.1% in September, and reached 0.8% in annual terms. However, the entire third quarter ended with a decline of 0.8% q/q, illustrating continued weakness in the sector. The manufacturing PMI remains at 48.2 points, indicating slight contraction. The strongest output growth was recorded in construction (+3.3% m/m), machinery (+2.8% m/m), and electronics and optics (+3.9% m/m). Weakness in the automotive industry (-1.2% m/m), which is a major contributor to German exports, continues to limit the potential for a broader sector-wide rebound.

Net exports continue to weigh on growth. According to DIW forecasts, export values will not increase in 2025, while import values are expected to rise by 1.4%, resulting in a negative net export contribution of -1.4 percentage points. Falling competitiveness in the automotive sector, geopolitical tensions, high energy costs, and a strong euro are constraining the prospects of a recovery in foreign trade. Without stronger demand from key economies, particularly China and the United States, German exports will remain a drag on overall economic growth.

The outlook for 2026 remains weak, and the expected rebound will be limited. Leading institutions anticipate only moderate improvement in Germany’s economic situation in 2026. The IMF estimates GDP growth at around 1.0%, a pace still clearly below that of most major EU economies. The European Commission forecasts growth of approximately 1.2%, pointing to a gradual recovery in euro-area demand, while emphasising that continued weakness in industry, particularly automotive, will remain a constraint on exports.

Jakub Ciunel

More Poles Are Leaving the United Kingdom

-19k net migration of Poles from the UK between June 2024 and June 2025

70k cumulative decline in the number of Poles living in the UK due to migration since 2020

-53.6% drop in net migration of non-EU nationals to the UK

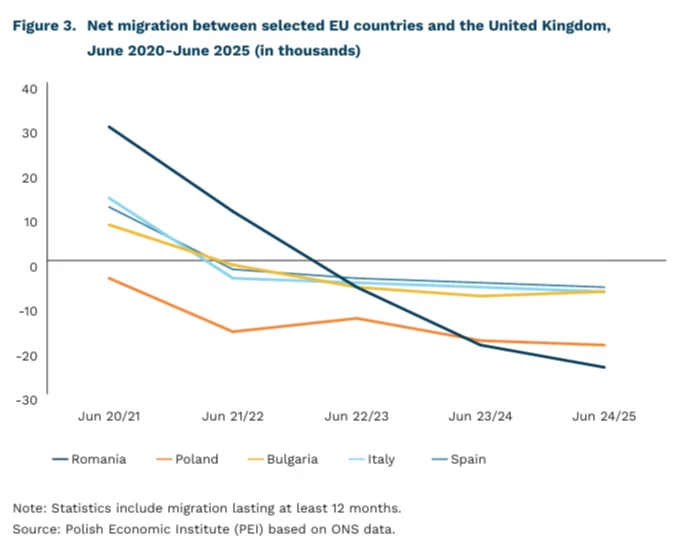

Between June 2024 and June 2025, around 6,000 Poles arrived in the UK, while approximately 25,000 left, according to preliminary ONS(1) data. Net migration of Poles to the UK amounted to -19,000, reflecting the broader trend of increased emigration from the UK among EU nationals. Over the same period, net migration of all EU citizens was -70,000, a decline of 9,000 compared with the previous year (-61,000). Between June 2020 and June 2025, the number of Poles living in the UK fell by a total of 70,000 due to migration. It remains unclear where those leaving the UK went next, as no data on their onward destinations is available.

The UK’s net migration balance with the EU has been declining since the Brexit referendum in June 2016. At that time, net migration amounted to 322,000 between June 2015 and June 2016 – the highest level in fourteen years. Net UK–EU migration fell below zero in June 2022, when 1,000 more EU citizens left the UK than arrived. By June 2023, the annual balance had reached -30,000.

Between June 2024 and June 2025, the UK recorded negative net migration for: Romania (-24,000), Poland (-19,000), Bulgaria (-7,000), Italy (-7,000), and Spain (-6,000). For all these countries except Bulgaria, the net balance deteriorated compared with the previous year.

Total long-term net migration (minimum 12 months) in the UK between June 2024 and June 2025 amounted to 204,000. This includes negative balances for EU citizens (-70,000) and British nationals (-109,000), while net migration of citizens from non-EU countries remained positive at 383,000. Among these, the largest contributors to net inflows were: Indians (69,000), Pakistanis (41,000), Chinese (25,000), Nepalese (22,000), Nigerians (18,000), and Americans (11,000).

The migration profile of the UK has shifted significantly over the past five years. After Brexit (January 2020), net migration from non-EU countries increased sharply. Between June 2020 and June 2021, it rose by 110% compared with the previous year, reaching 242,000 people. The highest annual figure for non-EU net migration was recorded in June 2023 at 1,045,000, before falling to 383,000 in June 2025 – a decline of 53.6% compared with June 2024 (825,000). This surge in migration from non-EU countries was driven by several factors: more liberal post-Brexit migration policies, a rise in the number of international students, the impact of the war in Ukraine, and the humanitarian route for Hong Kong residents.

According to the 2021 and 2022(2) censuses, approximately 804,000 Poles were living in the UK at that time. After accounting for net migration since then, an estimated 738,000 Poles remain in the country. The majority moved to the UK shortly after Poland joined the EU in 2004.

- Office for National Statistics.

- The 2021 census covered England and Wales, while the 2022 census covered Scotland.

Julian Kocerka

Growing Number of Energy Clusters as an Opportunity to Reduce Costs for Local Communities

12 energy clusters currently operating in Poland

Up to 300 sustainable energy areas (including energy clusters) planned to operate in Poland by 2030, according to the July 2025 draft update of the NECP

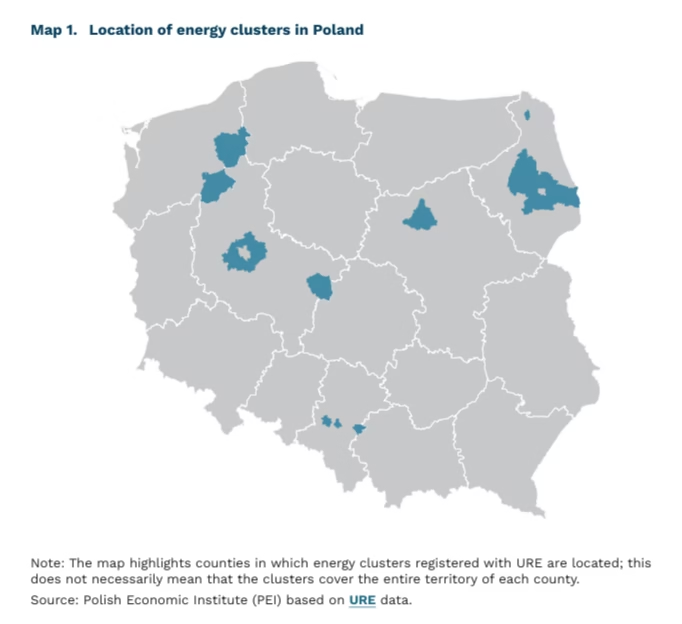

There are currently 12 energy clusters operating in Poland, according to the register of the Energy Regulatory Office (URE(3)). Energy clusters are a form of citizen energy, bringing together, among others, local government units, public institutions (such as schools), businesses, and renewable energy producers (as distinct from energy cooperatives, which may include individual consumers). These structures may cover an area of up to five municipalities or a single county, and their aim is to build the energy self-sufficiency of cluster members through low-emission production of energy (electricity, heat, cooling, and gaseous fuels) for their own needs.

The actual number of energy clusters in Poland may be higher, though it is difficult to determine precisely due to previous changes in their regulatory framework. Under the earlier definition used during the certification rounds carried out by the Ministry of Energy in 2017 and 2018, 66 such initiatives were identified. The seemingly lower number today stems from the fact that registration with URE is not mandatory, while some existing clusters may no longer meet the definition revised in 2023.

Despite moderate interest in establishing energy clusters in Poland, several barriers hinder their development. These include a high entry threshold in terms of organisational requirements and financial contributions from participants, insufficient incentives for creating clusters (e.g., exemptions from selected energy charges), and an underdeveloped settlement model for energy trading between cluster members.

Poland’s strategic documents – the NECP and PEP2040 – foresee an increasing role for local initiatives as the country’s energy transition progresses. Both policies assume that up to 300 sustainable energy areas, formed as energy clusters and energy cooperatives, may emerge by the end of the decade. Such structures deliver benefits both at the energy-system level, by aggregating flexible sources and loads, and for participating entities, by allowing them to reduce the cost of energy procurement. The latter advantage is particularly important given the negative impact of rising energy prices on the competitiveness of local businesses and municipal budgets.

Wojciech Żelisko

‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Can Be a Risky Consumption Pattern

10% increase in the quantity of goods purchased by BNPL users

6.4% increase in spending among consumers adopting BNPL services

Following the latest Black Friday, a number of reports and unofficial data indicated a significant share of purchases made through buy now, pay later (BNPL) schemes. The rapid spread of BNPL services has become one of the most notable financial developments of recent years, reshaping consumer decision-making patterns.

Empirical studies show that adopting BNPL as one’s shopping habit leads to immediate and substantial increases in spending. In one study, the authors analysed nearly 300,000 U.S. consumers, some of whom started using BNPL services. In the first few months of usage, these consumers purchased, on average, 10% more goods in terms of quantity. Other research finds a 6.42% increase in spending among consumers who adopt this form of payment.

Studies of Polish consumers show that BNPL usage is more likely among individuals with low income and lower levels of education. Similar patterns are observed in the United States. BNPL users are more likely to overdraw their bank accounts, rely on payday loans or pawnshops, and face increased risks of liquidity loss and accumulating debt – phenomena likely correlated due to the shared factor of low income. The core issue is that BNPL, despite being relatively financially attractive compared with high-interest payday loans, is psychologically more appealing than other short-term borrowing methods. As a result, it may encourage riskier financial behaviour among low-income consumers.

The appeal of BNPL stems from the psychological perception of cost. BNPL breaks payments into smaller instalments instead of focusing on the total cost, consumers perceive the instalments as if they were lower prices. Because the full payment is deferred, discounting mechanisms come into play: in decision psychology, a price paid in the future seems lower than the same price paid now. Combined with the immediate gratification associated with acquiring new goods, this increases the consumer surplus at the moment of purchase. Another psychological channel is a perceived sense of budget control: in an isolated shopping situation, BNPL gives the impression of a larger available budget, allowing consumers to purchase more than they would if they had to pay the full amount upfront. This contributes to a link between a BNPL usage and impulsive shopping, particularly pronounced among younger consumers.

Some countries have begun regulating the BNPL sector. The United Kingdom has announced that from 2026 new rules will enter into force, requiring, among other things, affordability assessments, creditworthiness checks, authorisation of BNPL providers by the appropriate authority, and clear, transparent information on BNPL terms. Similar regulations were introduced in the Netherlands, including stricter creditworthiness verification, greater transparency of repayment conditions, and mandatory age verification to prevent minors from using BNPL services. In Poland, rules are already in place restricting access to BNPL for individuals under 18 and requiring providers to verify consumers’ credit history and creditworthiness.

Łukasz Baszczak

Psychology Becomes the Most Popular Field of Study This Year

450.7k students admitted to higher education in 2025/2026

43.6k candidates who applied for psychology in 2025/2026

22.2 candidates per place for Oriental Studies – Japanese Studies in 2025/2026

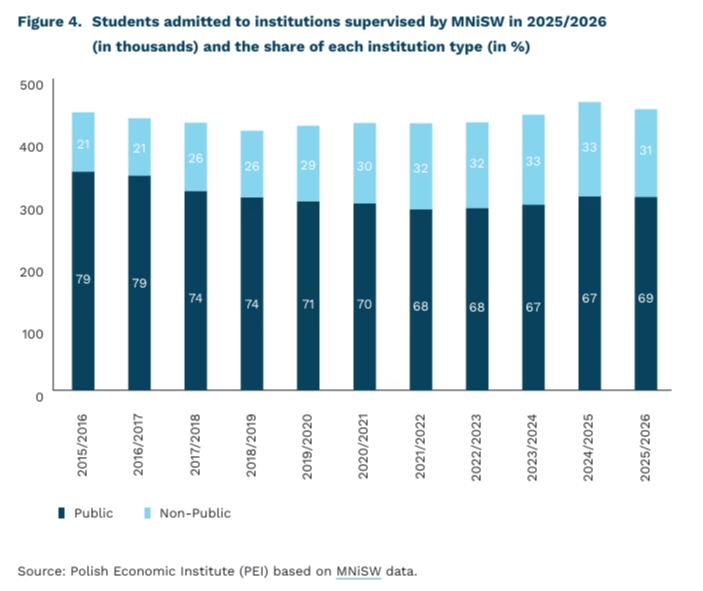

In the 2025/2026 academic year, 450.7 thousand students were admitted to the first year of studies at institutions supervised by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (MNiSW). Three-quarters enrolled in first-cycle or long-cycle programmes. Most students began their studies at public institutions (69%). However, compared with recruitment a decade earlier (2015/2016), the share of public institutions decreased by 10 percentage points.

Among public academic universities, the most popular were: the University of Warsaw (49k candidates), the Jagiellonian University (37k), the Warsaw University of Technology (33k) and the Gdańsk University of Technology (33k). Over the past ten years, these four institutions have consistently remained at the top in terms of applicant numbers. Among public vocational universities, the Tarnów Academy attracted the most interest (3k). The most frequently chosen non-public institutions were SWPS University (6k), Kozminski University in Warsaw (4.6k), WSB University (4.6k) and VIZJA University (4.5k).

Psychology was the most popular field, attracting 43.6 thousand candidates. Other top choices included medicine (30.6k), management (27.4k), law (26.4k), computer science (26.2k) and nursing (22.6k). Compared with a decade ago, the popularity of computer science and finance and accounting has declined, while psychology and medicine have seen a clear rise (at institutions supervised by MNiSW). Nursing and physiotherapy entered the top ten only three to four years ago.

The highest number of candidates per place was recorded in the following programmes: Oriental Studies – Japanese Studies (22.2), dentistry (18.0), Business and Management (17.7) and Business Data Science (16.3). Degree programmes focused on the languages and cultures of East Asia (Korean Studies, Sinology, Japanese Studies) have been popular for several years. At the same time, universities offer relatively few places in these fields, which drives up competition.

Choice of field is not always determined by expected earnings. According to graduate salary data from the ELA (Polish Graduate Tracking System) database, the fields attracting the greatest number of candidates and yielding above-average earnings include medicine, computer science, nursing, civil engineering and logistics. At the same time, not all popular fields align with labour-market shortages. Among the most popular fields that do correspond to shortage occupations in Poland are nursing and finance and accounting.

Anna Szymańska

Neoliberalism Has Created a New Global Middle Class – A Review of Branko Milanović’s The Great Global Transformation. National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World

The book The Great Global Transformation (Allen Lane, 2025) deliberately echoes Karl Polanyi’s classic work. In both cases, the central theme is free-market global capitalism. Whereas Polanyi criticised market fundamentalism as an unworkable and socially harmful utopia, Milanović emphasises the ways in which global neoliberalism, dominant since the 1980s, contained within itself the seeds of today’s transformation: the rising economic importance of Asia, the emergence of a new elite known as homoploutia, and the shift from global to national market liberalism.

Neoliberalism, alongside the growth of China and other Asian economies, contributed both to the emergence of a new global middle class at the expense of parts of the Western middle class and to the formation of homoploutia. This new elite includes individuals belonging simultaneously to the top 10% of labour income and the top 10% of capital income, marking a departure from classical capitalism, in which capital owners rarely worked in professional occupations. As a result, homoploutia resembles a self-reproducing aristocracy more than a system with a visible horizon of upward mobility for the middle class. In the United States, around 3% of the population belongs to this group; in Spain, Italy and Germany the share is 2-2.5%. China has also experienced a shift in elite composition. In 1988, most of the richest 5% derived their income from state employment. Three decades later, more than half earned their income in the private sector.

These internal transformations alone do not fully explain changes in foreign policy. Here, Milanović notes, theories of imperialism become helpful. Today’s US–China rivalry resembles that of the pre-1914 period. It is rooted in unequal distribution of national income and in an unstable order governing foreign investments driven by surpluses and high margins. What differs is the stake: no longer control of colonial trade, but the ability to set the rules of globalisation, and to modify them when they cease to serve the dominant power.

Inequalities have both domestic and global dimensions. Despite Asia’s growing significance, the income position of Western elites has remained stable, while the relative status of the Western middle class has declined. The deterioration of global consumption positions fuels resentment towards the establishment – resentment that benefits Trump. Milanović argues that the American “pivot to Asia” was driven not only by China’s rising power but also by threats to the status of elites shaped during the neoliberal globalisation era. In effect, internal factors – unequal income distribution, middle-class anger, and elite anxiety regarding their own position – are now driving the rivalry between the two leading powers.

The core argument is that global neoliberalism relied on US dominance and thus represented a hierarchical order. China, however, refuses a subordinated role and has challenged the system. Yet Milanović contends that the aims of China (and of Russia, which also rejects the current order) are defensive: the ability to uphold their own preferred models at the local or regional level. While ideological or cultural elements of neoliberalism can be replaced, Milanović argues that neoliberal economics itself remains robust. Lacking a coherent ideological-economic alternative, it is therefore likely to persist, albeit increasingly at the level of nation-states and regional alliances.

The book proves most compelling not in its main narrative, which at times consists of elements that do not fully cohere, but in its detailed insights: analysis of global income positions, diagnosis of the contemporary managerial class and its ideology, and references to theories of imperialism and uneven development. At the same time, Milanović tends to classify countries primarily by GDP per capita, overlooking the structure of the economy or control of value chains. From this perspective, the rise of countries such as Indonesia or Vietnam may prove fragile in the event of a major economic crisis – shocks that by nature affect the periphery more severely. Despite these reservations, this approximately 200-page book, rich in erudite nuances, certainly deserves several evenings of reading.

Filip Leśniewicz