30 years of the Maastricht Treaty: Central and Eastern Europe has converged with the “old” EU in development and institutions, but structural differences remain – PIE report shows

Key findings

Published: 17/01/2022

Between 1995 and 2020, the economies of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) grew on average by 3.1% annually, a pace more than three times faster than that of the so-called EU core countries. We observe clear institutional convergence, reflected in a fourfold reduction in differences between CEE countries and Western European countries in terms of legal standards, and a sevenfold reduction in differences in the level of economic freedom.

The situation looks different from the perspective of structural convergence, understood as the increasing similarity of economic structures. The pace of reduction in structural differences between the CEE region and EU core countries averaged only 0.2% per year, which means that despite significant socio-economic development in the region, structural differences within the European Union have remained almost at the same level as in 1995. These conclusions come from the Polish Economic Institute report “European Union: convergence or divisions? The European economy 30 years after the Maastricht Treaty.”

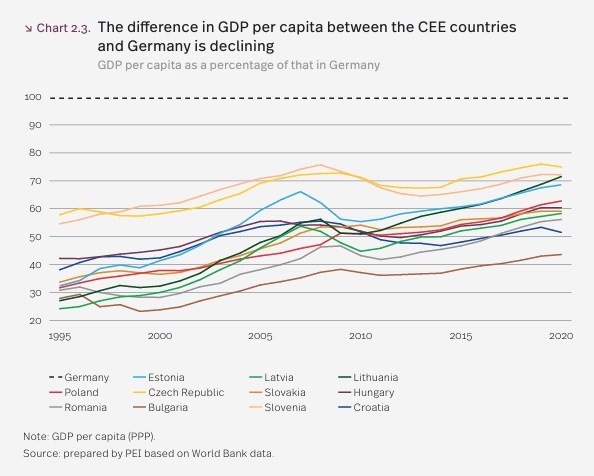

Economic convergence in the European Union is progressing. Over the past 25 years, the difference in GDP per capita levels between EU Member States has decreased by an average of 18%, according to the PIE report.

The biggest beneficiary of this process has been Central and Eastern Europe, which at the time of accession was the poorest part of the EU. Countries in this region recorded the fastest growth rates: between 1995 and 2020, GDP per capita increased on average by 5.1% in Lithuania, 3.9% in Poland, and 3.5% in Romania.

However, the pace of convergence would have been even faster if not for successive crises: the financial crisis more than a decade ago, the sovereign debt crisis of 2013, and the COVID-19 pandemic, all of which had a severe impact on the European economy. In the period 1995–2010, intra-EU development disparities were shrinking 2.5 times faster, says Prof. Krzysztof Marczewski, associate of the Macroeconomics Team at the Polish Economic Institute.

Spectacular pace of institutional convergence

Institutional convergence has proven to be the area of greatest success when assessing the Maastricht Treaty from the perspective of 30 years since its adoption. Today, it can be said that EU countries are broadly similar in terms of quality of law and levels of economic freedom, a trend that is particularly evident in Central and Eastern Europe.

Indicators show that differences between EU core countries and CEE states in legal quality have decreased nearly fourfold, while differences in economic freedom have fallen more than sevenfold.

Structural differences are harder to change

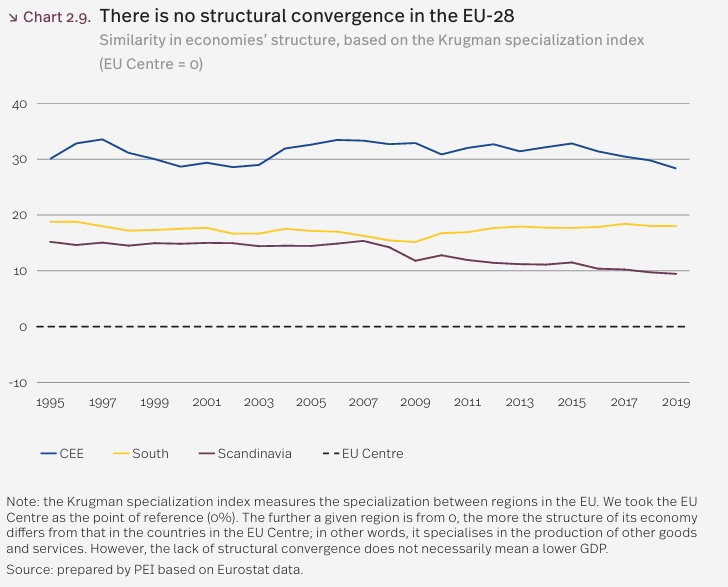

Structural convergence—understood as the increasing similarity of production structures across economies—is weakly visible in the EU. We observe the persistence of specialization, whereby different EU regions develop different branches of economic activity.

It is in this area that differences between CEE countries and the EU core are most pronounced. Structural differences between the economies of Central and Eastern Europe and the EU core remain almost twice as large as those observed between Southern European countries or the Nordic countries.

Between 1995 and 2019, the distance between CEE countries and the EU core narrowed by only 5.8% in total. In contrast, in Scandinavia, differences in production structures declined by as much as 38% over the same period.

Central and Eastern Europe has undoubtedly made a significant developmental leap. However, it should be remembered that this progress was based primarily on a reduction in the role of agriculture, the transformation of the industrial sector, and its adaptation to the technological and economic requirements of modern international competition.

Despite these changes, a number of structural parameters, such as wage levels, adjust much more slowly. Only the development of an innovation-driven, knowledge-based economy—in particular the modern services sector—offers hope for fuller economic convergence with the most advanced EU countries, says Marcin Klucznik, analyst in the Macroeconomics Team at the Polish Economic Institute.

***

The Polish Economic Institute is a public economic think tank with a history dating back to 1928. Its main research areas include foreign trade, macroeconomics, energy, and the digital economy, as well as strategic analyses of key areas of social and public life in Poland. The Institute prepares analyses and expert studies supporting the implementation of the Strategy for Responsible Development and promotes Polish research in economic and social sciences domestically and internationally.

Media contact:

Ewa Balicka-Sawiak

Press Officer

T: +48 727 427 918

E: ewa.balicka@pie.net.pl