As many as 700 million people live in the countries where food security is the most threatened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

Published: 30/06/2022

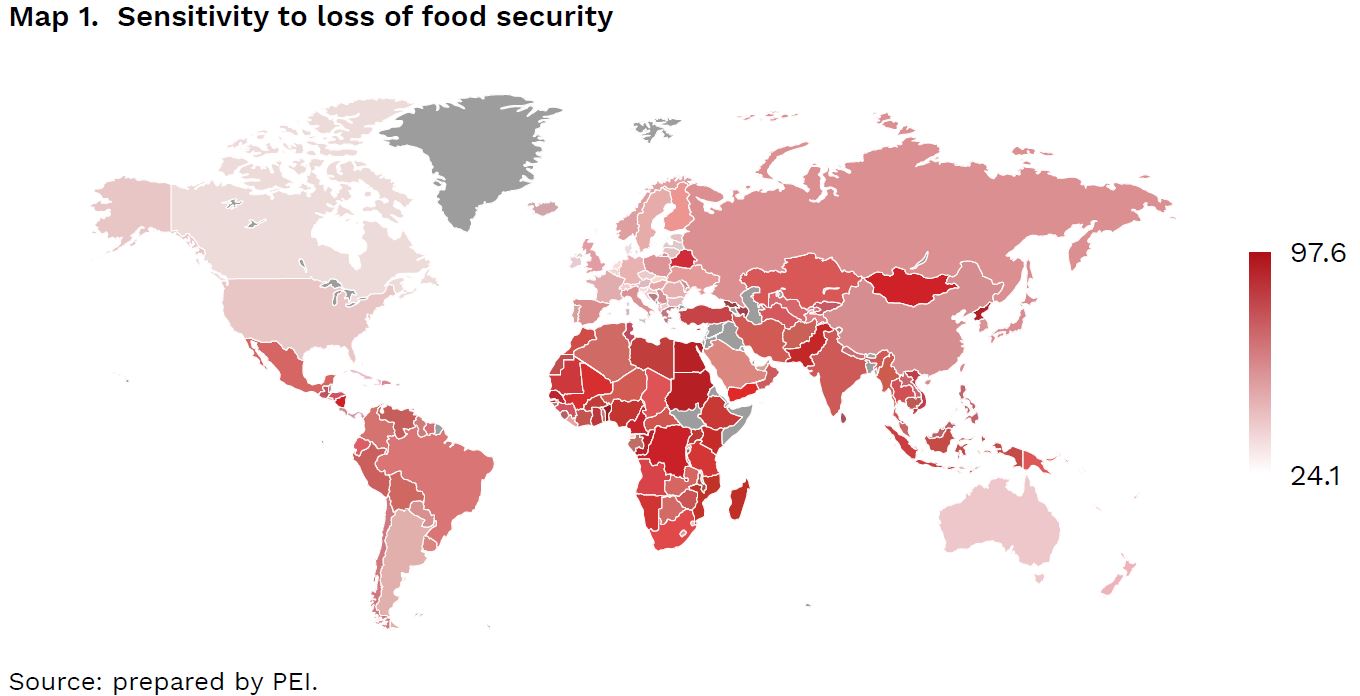

The sensitivity index (SI) created by the Polish Economic Institute shows that the following countries’ food security is the most threatened as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: Benin (SI = 97.6), North Korea (SI = 97.3), Sudan (SI = 92.5), Nicaragua (SI = 90.8) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (SI = 89.8), followed by Armenia, Egypt, Lebanon, Georgia, and Rwanda.

To describe each country’s sensitivity to a potential food crisis, the Polish Economic Institute developed a sensitivity index (SI) made up of four components: a country’s self-sufficiency when it comes to growing wheat, Ukraine and Russia’s share in the country’s wheat imports, the share of grains and root crops in the country’s energy balance and the value of the GDP per capita.

“Our results confirm the widespread feeling that the Russian invasion could lead to a serious food crisis, which will particularly affect poorer countries dependent on grain and other food imports from Russia and Ukraine, as well as those in Africa and the Middle. Yet we will also experience disruption in our part of the world. The Russian invasion and drought in Europe and beyond mean that food prices could be over 20% higher than a year ago after the summer holidays, which will further drive inflation in Europe,” said Marek Wąsiński, head of the global economy team at the Polish Economic Institute.

“Russia is responsible for the ongoing food crisis – not only because of the invasion, which has led to the collapse of the Ukrainian economy, but also due to targeted measures on agricultural and food markets. Russia is stealing grain from Ukraine, destroying food warehouses, and blocking Ukrainian ports, which had previously exported agricultural and food products. Many African and Asian countries were more dependent on wheat imports from Russia than those from Ukraine. The Kremlin is also restricting exports to achieve political goals, including by triggering a food crisis and accusing the West of causing it. At the same time, the high prices are conducive to higher revenue from exports,” said Jan Strzelecki, deputy head of the global economy team at the Polish Economic Institute.

The spectre of hunger

Benin, Mongolia, Armenia, North Korea, Sudan, Lebanon, and Belarus import over 90% of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine. The food security of these countries, along with that of Nicaragua, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Georgia, and Rwanda, is the most at risk as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They are the most likely to struggle to ensure the physical supply of food.

The indirect consequences of the Russian invasion, in the form of rising food prices, are even more important. The war has destabilised agricultural and food markets: in March 2022, the global food prices index rose to 159.3 points (by 12.6% month on month), its highest-ever level, and only decreased slightly in May, to 157.4 points. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the number of malnourished people could increase by as much as 13 million in 2022-2023.

How can the international community respond to threats to food security?

Firstly, to avoid a global food crisis, the international community needs to take action to unblock the transport corridors leading through the Black Sea. In addition, it is crucial to increase grain production, either by increasing crop acreage or by improving the yield per hectare of crops. Rising commodity prices and the shortage of quality agricultural land mean that there is limited scope for action here.

The international community should therefore counteract any kinds of processes that threaten food security in relatively low-income countries. The war and uncertainty are destabilising the food market, and speculative actions are pushing up prices further. Even after the war ends, food prices will not fall rapidly; rather, they will remain high.

***

The Polish Economic Institute is a public economic think tank dating back to 1928. Its research primarily spans macroeconomics, energy and climate, foreign trade, economic foresight, the digital economy, and behavioural economics. The Institute provides reports, analyses, and recommendations for key areas of the economy and social life in Poland, taking into account the international situation.

Media contact:

Ewa Balicka-Sawiak

Press Spokesperson

T: +48 727 427 918

E: ewa.balicka@pie.net.pl

Kategoria: Press releases / Report / Reports 2022 / Russia's invasion of Ukraine