Economic Weekly 37/2025, September 19, 2025

Published: 19/09/2025

Table of contents

One in Three Sole Proprietorships in 2024 Was Established by an Entrepreneur Under 30

30% share of all new sole proprietorships (JDG) in Poland in 2024 founded by people under 30

15 per 1,000 youth entrepreneurship rate (new JDG registrations among people under 30) in 2024

6.7% unemployment rate among people aged 15-29 in 2024

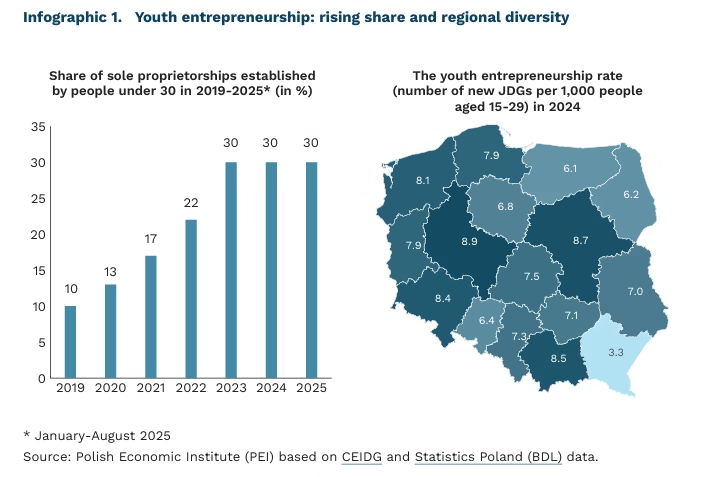

Between January and August 2025, nearly one in three (30%) newly established JDGs was registered by an entrepreneur under the age of 30, according to CEIDG data. The number of JDGs set up by people under 30 has been steadily increasing: in 2019, young entrepreneurs registered 30,300 such businesses (10% of all new registrations), while in 2024 the figure reached 86,300, i.e. 30% of all new JDGs. This rise may be partly linked to the growing practice of offering employees B2B contracts, which allow firms to optimise labour costs and tax burdens. Additional incentives came from tax breaks available to young entrepreneurs.

In 2024, there were 15 newly registered JDGs per 1,000 people under the age of 30 – three times more than in 2019, when the figure stood at just 5 per 1,000. The youth entrepreneurship rate (number of new JDGs per 1,000 people aged 15-29) provides a clearer picture of entrepreneurial activity than the percentage share alone, as it relates the number of new businesses to the entire population in this age group. The sharp increase highlights the growing propensity of young adults to start their own business.

In 2024, youth entrepreneurship was highest in the voivodships of Wielkopolskie (8.9 sole proprietorships per 1,000 people aged 15-29), Mazowieckie (8.7) and Małopolskie (8.5). The lowest rate was observed in Podkarpackie, with 3.3 per 1,000 young adults. Regional differences are also visible in the share of young adults among all sole proprietorship founders. The highest shares were recorded in Lubelskie, Wielkopolskie and Podkarpackie (32%, 30% and 29% respectively). In Lubuskie, one in four new sole proprietorships was registered by someone under 30. High entrepreneurial activity among young adults is observed both in regions with low unemployment (Małopolskie, Wielkopolskie) and those with relatively high unemployment (Lubelskie, Dolnośląskie). This suggests that in some regions self-employment is aspirational and developmental, while in others it plays an adaptive role, serving as an entry point to the labour market.

People under 30 face greater challenges in the labour market, experiencing higher unemployment than the general population. In 2024, the unemployment rate in Poland stood at 2.9%, while among those aged 15-29 it was more than twice as high at 6.7%, according to the Labour Force Survey (LFS, Polish: BAEL). Registered unemployment data show that in July 2025, nearly 24% of the unemployed were under 30. In such conditions, some young adults set up their own business not out of entrepreneurial ambition, but out of necessity – as a prerequisite for employment and income. For many, it is the only available way to enter the labour market when access to traditional employment is limited.

At the same time, self-employment can also be a conscious choice – a way to gain experience, shape one’s career and enjoy greater independence. Higher risk tolerance, greater flexibility and a longer time horizon allow young people to experiment with their careers, treating potential failures as part of the learning process. Beyond being an individual career path, self-employment also acts as a mechanism to reduce the risk of inactivity and exclusion from the labour market in the form of NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training).

Aleksandra Wejt-Knyżewska

Global Use of Low-Emission Hydrogen Grows Despite Development Barriers

100 million tonnes global hydrogen demand at the end of 2024

Below 1% share of low-emission production methods (water electrolysis and steam methane reforming with CO₂ capture) in global hydrogen output

10% share of Poland in EU hydrogen production in 2023 (729 out of 7,265 thousand tonnes)

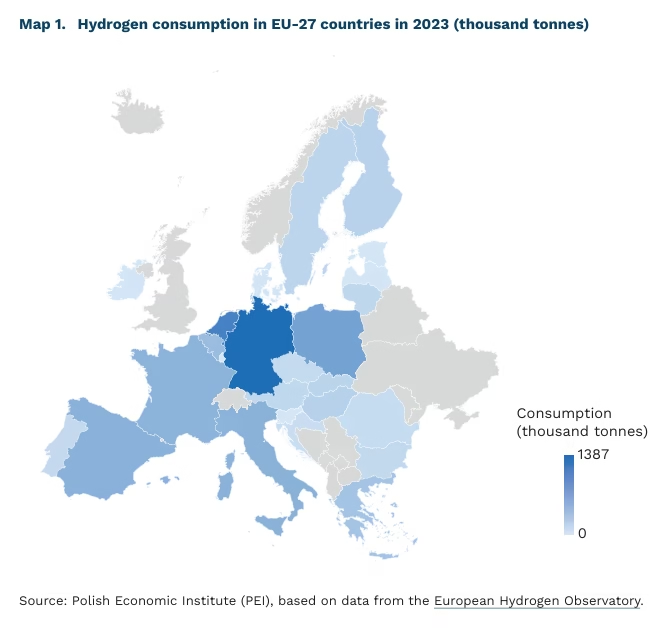

In 2024, global hydrogen consumption reached 100 million tonnes, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Over the past five years (2020-2024), demand increased by 10%, but almost exclusively in traditional applications in the refining and chemical sectors. New uses such as road and maritime transport and low-emission production methods (water electrolysis and steam methane reforming with CO₂ capture) still account for less than 1% of total consumption and production of this fuel.

The global hydrogen economy has so far developed more slowly than anticipated in earlier forecasts and policy targets. Key barriers include the slower-than-expected decline in electrolyser costs, difficulties in securing demand for low-emission hydrogen, insufficient or poorly designed regulation, and the lack of accompanying infrastructure for transport and storage. These factors mean that low-emission hydrogen projects are often delayed or cancelled, and few reach a final investment decision (FID) that would give them the green light for implementation.

Poland, as the EU’s third-largest hydrogen producer, also recognises the potential of hydrogen for decarbonising the economy, but its role is unlikely to expand significantly before the end of this decade. According to the Hydrogen Map of Poland study, conducted by Gaz-System in 2024, the national potential for low-emission hydrogen production and consumption in 2030 is estimated at 0.5 million tonnes and 1.3 million tonnes, respectively. However, most projects are still at the preliminary analysis stage. Production facilities are planned mainly in north-western Poland, while hydrogen-consuming installations are expected to be spread across the country. The mismatch between supply and demand, combined with the lack of coordination in project locations, underscores the need to expand transmission and storage infrastructure as well as to explore import opportunities from third countries.

The Polish Hydrogen Strategy foresees the installation of 2 GW of electrolysers by 2030 – equivalent to the entire global capacity in place at the end of 2024. Meanwhile, projects submitted under the Hydrogen Map of Poland suggest a potential of 5.6 GW by the end of the decade. Given the early stage of these projects and the uncoordinated development of supply and demand, this figure should be treated more as an ambition than a firm commitment. It is therefore unlikely that Poland will meet the EU’s targets for renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs), which require broader use of low-emission hydrogen in transport and industry. This challenge is confirmed by Poland’s National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), which estimates domestic production potential in 2030 at 122 thousand tonnes against a projected demand of 315 thousand tonnes in line with RFNBO targets.

Wojciech Żelisko

Poland Climbs Higher in the Global Innovation Index 2025

39th place Poland’s position in the Global Innovation Index 2025 (WIPO)

40th place Poland’s position in the Global Innovation Index 2024

15 number of European economies among the top 25 in the ranking

11th place Poland’s ranking for industrial diversification

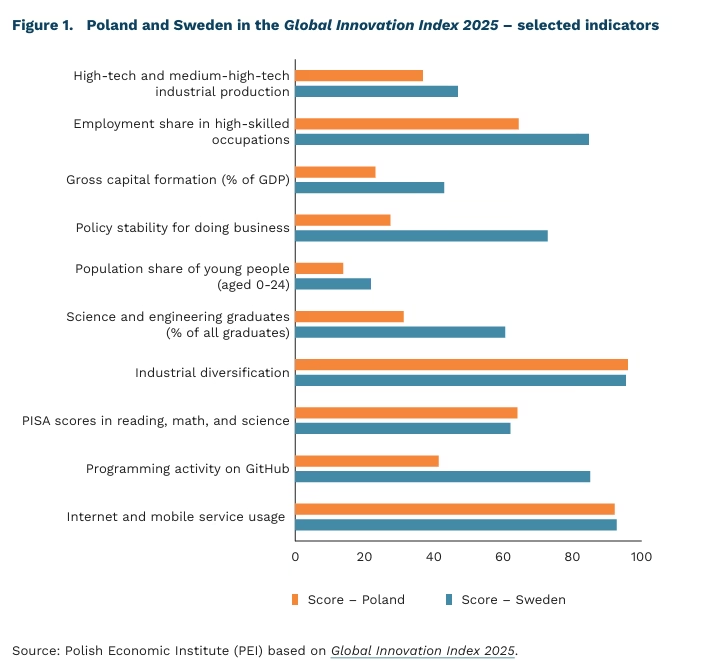

Poland ranked 39th in the 2025 edition of the Global Innovation Index (GII), published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The index aims to provide a comprehensive picture of innovation, capturing social transformation, shifts in business models, institutional organisation, and technological progress. Poland was placed just behind India and ahead of Croatia, Lithuania, Greece, and Turkey. Switzerland topped the ranking for the fifth consecutive year (2021-2025), followed by Sweden, the United States, South Korea, and Singapore. From a regional perspective, Europe remains the leading area, with 15 European economies ranked among the world’s 25 most innovative, including six in the top 10.

Poland is among the most diversified economies in Europe, ranking 11th worldwide in terms of industrial diversification (measured by the share of individual sectors in total industrial output). Other areas of strength include the share of creative goods in total trade (13th), digital economy indicators (internet and mobile service usage – 15th; intensity of programming activity on GitHub – 26th), and human capital (PISA scores for 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics, and science – 14th; share of researchers in business sector employment – 18th). By contrast, weaker results were recorded for the share of young people in the total population (124th), the stability of the political environment for business (109th), and investment in fixed assets and inventories (108th).

Although the index is presented as comprehensive, it overlooks two key dimensions of development: control over value and the conditions and distribution of work. The GII does not address who creates and who ultimately captures the surplus generated by innovation. It frames innovation as the domain of countries, whereas in practice it is global corporations that largely carry out innovative activities worldwide, often relying on local labour and infrastructure. The ultimate benefits, i.e. intellectual property rights, profits, and control over technologies, remain concentrated within corporations (for example, Samsung Electronics was the largest patent applicant in Warsaw). Moreover, the index does not reveal whether innovation in a given country increases labour’s share of value added or whether median wages keep pace with productivity. As a result, it remains unclear whether the gains from innovation support broad social welfare or primarily benefit narrow groups of specialised workers and capital owners.

Indices such as the GII always provide a partial view and should not be treated as an end in themselves for public policy. They can be useful, but require careful interpretation and should be complemented with a structural perspective and additional indicators ref lecting working conditions and the distribution of benefits.

Filip Leśniewicz

Poland Has One of the Lowest Job Turnover Rates Among European Countries

10.6% share of employees in Poland working in their current job for less than a year

19.5% share of employees in Spain working in their current job for less than a year

22.3% share of employees in Norway working in their current job for less than a year

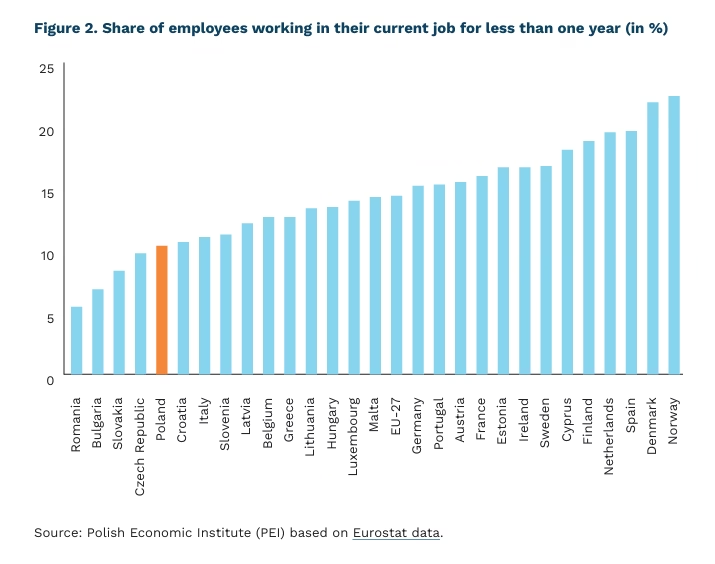

In Poland, only 10.6% of employees are newly hired, i.e. working in their current job for less than one year. This is significantly lower than in most other European countries. Northern European countries are among those with the highest turnover rates, close to 20%. The indicator stands at 18.7% in Finland, 21.8% in Denmark, and 22.3% in Norway. Spain also records a very high level of turnover (19.5%), which can likely be explained by the rebound from a prolonged economic crisis. The economic recovery has been accompanied by job creation, which in turn increases the share of newly employed workers in total employment.

The data show that employees in Poland rarely change jobs. It is noteworthy that post-communist countries have significantly lower turnover rates compared to the so called ‘old’ EU member states. This may stem from the relatively short period of operating within an open labor market, which fosters, or even necessitates, greater occupational mobility.

The dominant model of long-term employment in a single workplace in Poland, while beneficial in terms of life stability, may also have adverse effects, particularly with respect to employees’ limited engagement in professional development. Research indicates that Poland’s low participation rate in training, among the lowest in Europe, can partly be explained by the fact that employees are seldom motivated by the prospect of finding a better job, improving their career situation, or acquiring new skills. According to the 2023 PIAAC survey, only 10% of Polish employees participated in non-formal training for these reasons – a rate considerably lower than in other surveyed countries.

Paula Kukołowicz

Higher Education Pays Off More for Polish Men than for Polish Women

31% share of Poles aged 25-34 with a master’s degree or higher

54% average wage premium for Poles with higher education compared to those without

72% average earnings of Polish women with a bachelor’s degree or higher, relative to men with the same level of education

According to the latest Education at Glance 2025 report, Poland ranks second among OECD countries in the share of citizens holding a master’s degree or higher. In 2024, this share stood at 31% of the population aged 25-34, surpassed only by Luxembourg.

Compared to other countries, Poles relatively often continue their studies beyond the bachelor’s level. The share of 25-34-year-olds in Poland with a master’s degree or higher is twice the OECD average (16%) and significantly above the EU average (21%). However, when bachelor’s degrees are included, the overall share of tertiary-educated individuals in Poland (46%) is slightly below the OECD average (48%) and broadly in line with the EU average (45%). This share has increased since 2019, both in Poland and across most countries.

Highly educated individuals also enjoy better labour market prospects in Poland. Unemployment among those with higher education is among the lowest in the OECD, with the rate more than twice as low as the EU and OECD averages.

Earnings for Poles with higher education are, on average, 54% higher than for workers without it (full-time employees, aged 25 and over). Among younger workers (25-34), however, the wage premium drops to 37%. Both figures are only marginally above the OECD and EU averages.

Pursuing higher education is relatively less rewarding for women in Poland than in other countries. On average, Polish women with higher education earn 72% of the wages of men with the same education level. This gender pay gap is among the largest across OECD countries and 5 percentage points wider than the EU average (77%).

Łukasz Baszczak

More Europe in Europe – The Economic Dimension of von der Leyen’s Address

‘Europe must accelerate’, this was the key message of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in her annual State of the Union address. Her speech focused on security and support for Ukraine, boosting economic competitiveness, regulations to strengthen European industry, innovation, and responses to pressing social challenges. Below we highlight selected economic announcements that will shape the EU’s course in the coming years.

Von der Leyen called for the promotion of European production in public procurement. In her State of the Union address on 10 September, she announced the introduction of a ‘Made in Europe’ criterion in EU tenders. She placed particular emphasis on the clean tech sector, though the measure could extend beyond it. Public procurement is one of the few areas that may fall under a legal exemption from WTO rules, making such requirements possible. In 2017, foreign companies accounted for 14% of EU public contracts (EUR 50 billion). She also underlined plans to create strong incentives for buying European goods and services within EU development aid and investment projects in third countries.

One possible fast-track mechanism for introducing ‘Made in Europe’ is through upcoming industrial regulations. By the end of the year, the Commission plans to present the Industrial Accelerator Act. In her address, von der Leyen dropped the term Decarbonisation from its title, broadening the scope beyond clean tech and energy-intensive sectors. The planned regulation will introduce accelerated permitting procedures to modernise production processes and may also include criteria favouring European suppliers.

A European electric car as a response to growing competition from China. The announcement of a European-made electric vehicle should be seen in the broader context of strengthening Europe’s industrial competitiveness. Foreign manufacturers, particularly from China, are rapidly gaining ground in the EU electric vehicle market. In the first half of 2025, China accounted for 41% of EU electric car imports, even though EU tariffs reduced the value of imports by 27% year-on-year. Their main advantage lies in pricing: Chinese models are on average several thousand EUR cheaper than comparable European vehicles (T&E, BloombergNEF). In response, the European Commission unveiled the Small Affordable Cars initiative, aimed at producing compact EVs priced between EUR 15,000 and 25,000, to compete effectively with imports. The initiative will be supported through regulation and public procurement, including municipal fleets and public transport favouring ‘Made in Europe’ vehicles, stricter CO₂ standards, and incentives for local battery production and supply chains.

A European housing plan to improve affordability and curb short-term rentals. Housing shortages and soaring prices remain a pressing challenge across the EU. According to Eurostat, between 2010 and Q1 2025 housing prices in the EU rose by 58%, while rents increased by 28% – in Poland, the figure for housing prices reached +102%. In response, the Commission announced the first European Housing Summit and a European Housing Plan, under which EIB financing will rise to EUR 4.3 billion in 2025 (+40% vs. 2023). At the same time, the Commission is drafting regulation of the short-term rental market, a significant issue in large cities where platforms like Airbnb reduce housing availability and drive up rents. Across the EU, 854 million overnight stays were booked through such platforms in 2024 (+18.8% y/y).

The Choose Europe programme to retain and attract talent. Brussels aims not only to foster innovation but also to retain researchers in Europe and attract talent from abroad. The new Choose Europe programme will provide EUR 500 million in 2025-2027 for ERC super-grants, relocation support, and special career tracks for researchers who might otherwise leave for the US or Asia. For comparison, the annual budget of the European Research Council stands at EUR 2.2 billion.

Regulatory and financial support for European firms. Following the recommendations of the Letta and Draghi reports and the newly announced Competitiveness Compass, Von der Leyen announced the creation of demand-support funds within the EU (e.g. EUR 1.8 billion for batteries), as well as the establishment of a Scaleup Europe Fund to boost equity investments in high-tech companies. She also recalled the initiative of a 28th EU legal regime for companies, aimed at reducing barriers and discriminatory effects within the single market. These measures are linked to the creation of a Savings and Investment Union, as advocated in the Letta report.

Marek Wąsiński, Sebastian Sajnóg