Economic Weekly 19/2025, May 16, 2025

Published: 16/05/2025

Table of contents

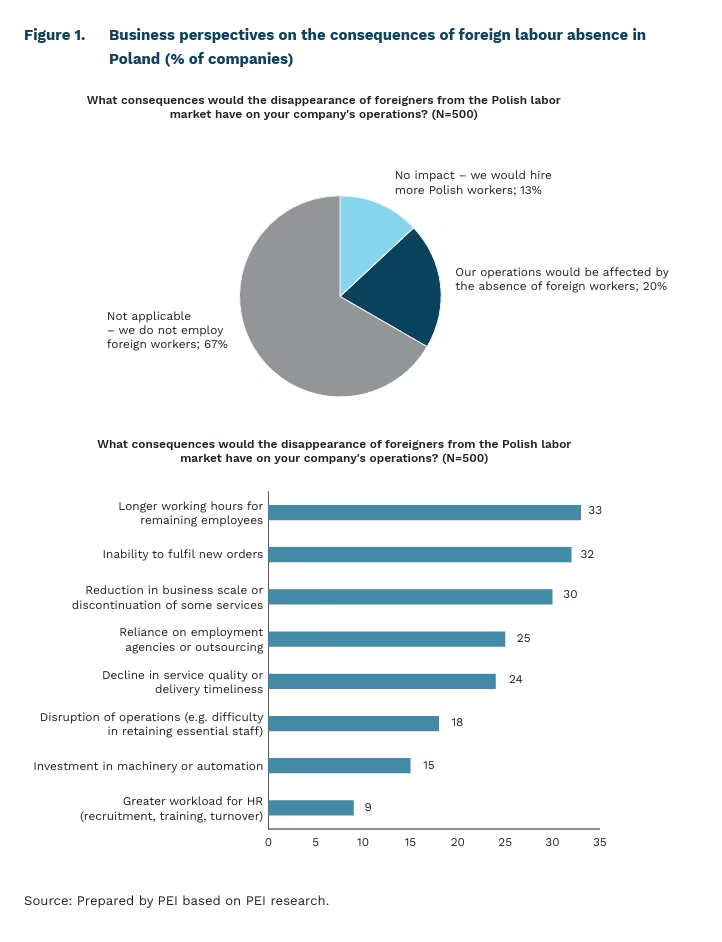

One in Five Polish Companies Would Struggle Without Foreign Workers

1/3 of companies surveyed by the Polish Economic Institute (PEI) employ foreign workers

30% of companies that would be affected by reduced access to foreign labour report they would need to scale back their operations or discontinue some of their services

15% of such companies would respond to restrictions on employing foreigners by investing in machinery and automation to replace foreign workers

Between 2022 and 2024, the number of foreign workers in Poland increased by 33%, according to data from the Central Statistical Office GUS. As of the end of March 2025, 1,210,027 individuals insured with the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS), eclared a nationality other than Polish in their pension insurance records. The vast majority (94%) are employed under an employment contract, a contract of mandate, or an agency agreement. The remaining 6% are self-employed in non-agricultural business activities. By the end of 2024, foreigners accounted for 7.3% of all natural persons insured with ZUS.

A PEI survey conducted in May 2025 found that approximately one-third of the 500 companies surveyed employ foreign workers, primarily among large (50%) and medium-sized (47%) enterprises. In small companies, this figure is 35%, and in micro-enterprises only 22%. Foreigners are most commonly employed in the transport, forwarding, and logistics (TFL) sector (46%), followed by industry (40%) and construction (36%). In trade and services, the share is 23%.

In the survey, entrepreneurs were asked to consider a hypothetical scenario in which all foreign workers were to leave the Polish labour market. The results show that one in f ive companies would be affected by the absence of foreign workers. Only 13% of firms said they could manage the situation by hiring more Polish workers. The remaining 67% are companies that currently do not employ foreigners and therefore would not be impacted by this scenario.

The absence of foreign workers from the Polish labour market would result in longer working hours for remaining employees—this is the concern of one in three companies that anticipate consequences if foreign labour were no longer available. 32% of firms fear they would be unable to fulfil orders, while 30% report they would need to scale back operations or discontinue some services, particularly in the construction and transport, shipping, and logistics (TFL) sectors. 24% anticipate a decline in service quality or delays in delivery, especially in trade and TFL. For 18% of companies, mainly in manufacturing and TFL, the absence of foreign workers threatens the continuity of operations. 15% of businesses, predominantly in manufacturing, say they would consider replacing foreign labour through investment in automation.

Foreign workers play a vital role in the Polish labour market, as confirmed by both statistical data and employer sentiment. Their hypothetical disappearance would carry serious consequences for many firms, from difficulties in meeting demand and declining service standards to the need to scale down activity. Only a small share of companies would be able to easily replace them with Polish workers. Macroeconomic data shows that between 2021 and 2023, the average contribution of immigrant labour to Poland’s annual GDP growth was 0.5 p.p., accounting for approximately 18% of total growth. According to OECD, analyses, foreign workers are key to addressing labour shortages in in-demand occupations, particularly in countries with growing employment needs such as Poland. These f indings underscore that foreign workers are an essential and, in many cases, irreplaceable part of the Polish labour market.

Katarzyna Dębkowska

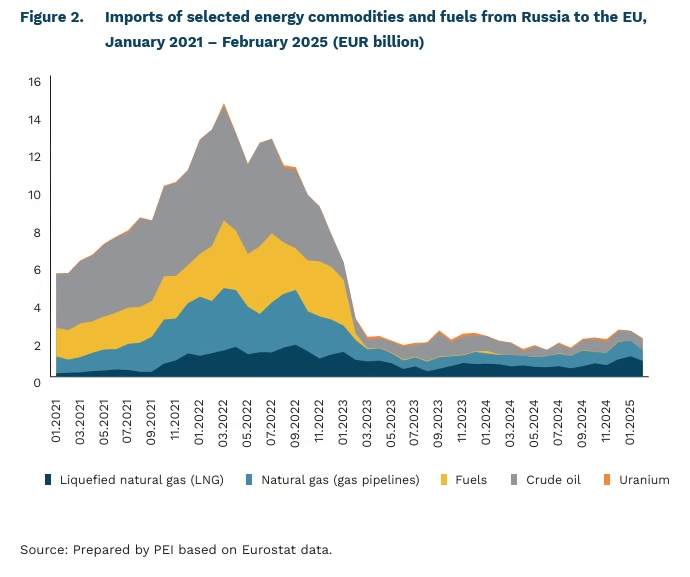

Russia Earns EUR 61 Million Daily from Oil, Gas, and Uranium Exports to the EU

EUR 61 million per day was earned by Russia in 2024 from oil, fuel, gas, and uranium exports to the EU

27% the projected share of oil, gas, and fuel tax revenues in Russia’s 2025 federal budget

4 times less Russian gas is expected to be imported by the EU in 2025 compared to 2021, according to the European Commission

Roadmap towards ending Russian energy imports outlines a proposed timeline for phasing out Russian oil and gas by the end of 2027 and for reducing the EU’s reliance on imports of Russian uranium. Published by the European Commission on 6 May 2025, the roadmap is the outcome of a lengthy negotiation process among Member States. Its release was originally planned for February 2025 but was delayed multiple times due to opposition from countries heavily dependent on Russian fossil fuels, particularly Hungary and Slovakia. The document also signals more decisive measures to come, which will be detailed in a separate plan to be unveiled in June 2025. While the value of Russian exports of gas, oil, fuels and uranium to the EU dropped by 25% in 2024 compared to 2023, was six times lower than in 2022 and four times lower than in 2021, Russia still earned more than EUR 61 million per day from these exports last year.

In 2024, the value of Russian gas exports to the EU was more than twice that of crude oil and fuels, and 20 times higher than the value of Russian uranium exports. This is why phasing out Russian gas remains a priority for the European Commission. By the end of 2025, a ban on the purchase of Russian gas through short-term spot contracts, currently accounting for about 33% of Russian gas exports, is expected to take effect. Member States are also required to submit national plans for phasing out Russian gas imports, including timelines for terminating long-term contracts, all of which are to end by 2027. Sanctions on Russian crude oil and petroleum products are also set to be tightened. However, ending imports of enriched uranium may prove more challenging due to the EU’s limited production capacity after years of underinvestment. Although annual imports of Russian uranium are valued at only around EUR 700 million, the product is strategically important: as much as 24% of the enriched uranium used in the EU comes from Russia.

Russia is facing serious economic challenges, as global oil prices dropping to as low as USD 50 per barrel have forced Moscow to revise its budget. With o, These changes may lead to the largest deficit since the pandemic. Revenues from oil, gas, and petroleum product exports were expected to make up 27% of Russia’s 2025 budget. However, in the first quarter alone, these revenues were already 8% lower than during the same period in 2024. According to estimates from the Russian Ministry of Finance, such revenues are expected to decline by 24% year-on-year in 2025, resulting in a projected 6.5% drop in total federal income. The Ministry, has indicated that this may require substantial cuts to planned expenditures. Meanwhile, economic growth is slowing: Rosstat data on industrial production show that both energy and non-military sectors are losing momentum. As a result, even official forecasts from the Russian Central Bank and the Ministry of Economic Development predict a sharp deceleration, with growth expected to fall to between 1% and 2.5% in 2025.

Jan Strzelecki, Kamil Lipiński

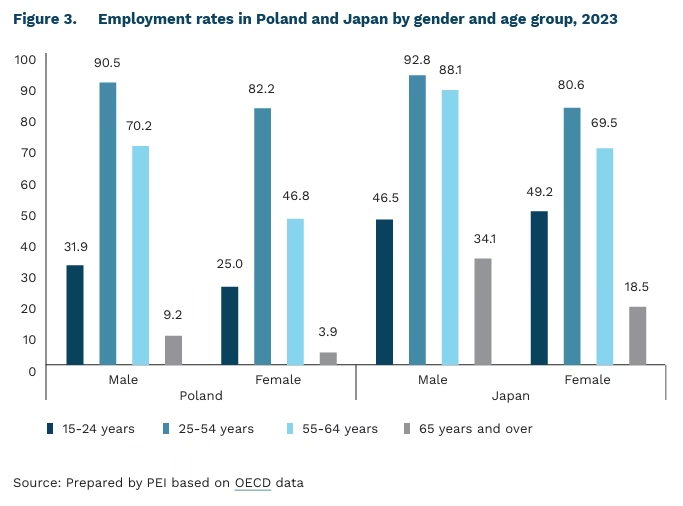

Japan Sets a Good Example in Managing an Ageing Society

29.2% of Japan’s population was aged 65 and over in 2023, reflecting the country’s old-age dependency ratio

25.3% was the employment rate for people aged over 65 in Japan in 2023

30% of Japan’s taxi and bus drivers are aged 65 or older

Poland is entering a period of rapid population ageing, a process Japan has been experiencing for much longer. Japan’s total fertility rate (TFR) fell below the replacement level of 2.1 in 1957, whereas in Poland this occurred in 1989. Since the mid-1990s, the TFR in both countries has remained similarly low. – 1.11 in Poland and 1.16 in Japan in 2024. However, Poland’s fertility decline was steeper and unfolded over a shorter period compared to Japan.

Japan and Poland are at different stages of demographic ageing, but the overall trend is similar. In 2023, the old-age dependency ratio – defined as the share of people aged 65 and over in the total population — stood at 29.2% in Japan and 20.1%(1) in Poland. Since 2010, this ratio has grown at a comparable pace in both countries, rising by 6.2 p.p. in Japan and by 6.6 p.p. in Poland. Meanwhile, the demographic ageing index(2) (i.e. the ratio of people aged 65 and over to children aged 0–14) increased in Japan from 1.75 in 2010 to 2.57 in 2023). In Poland, the index reflects the early phase of demographic ageing, rising from 0.88 to 1.33 over the same period.

Japan has made significant progress in mitigating the negative effects of an ageing population. A key measure has been boosting labour force participation to counteract a shrinking workforce. In 2024, Japan recorded the highest employment rate among G7 countries and one of the highest female employment rates across the OECD. The effective retirement age(3) in Japan is also the highest among OECD member states.

The employment rate among younger people (aged 15–24) and older adults (aged 55 and over) in Poland is significantly lower than in Japan. Among those aged 25–54, however, the employment rates are nearly identical: 86.4% in Poland and 86.8% in Japan. Notably, in this age group, the employment rate for women is slightly higher in Poland than in Japan, while for men it is lower.

In 2013, the Japanese government launched its Womenomics policy, which led to a rise in the female employment rate. The policy included the expansion of childcare infrastructure and flexible working arrangements, the extension and promotion of parental leave, incentives for companies to hire and promote women, measures to combat workplace discrimination, and public campaigns aimed at challenging gender stereotypes and promoting equal opportunities in both professional and family life. Initially, the increase in women’s employment was driven by part-time roles, but in recent years the proportion of full-time employment has also grown. As such, concerns that informal family care responsibilities hinder women’s participation in the labour market appear to be unfounded. A well-developed public social care system, including elderly care, is essential.

The continued participation of a large proportion of the Japanese population in the labour market rests on two key factors. First is the high share of people in good health. Second is a well-developed labour market for older adults, which not only offers employment opportunities but is also supported by an appropriate pension system and regulations that facilitate job creation. Older workers in Japan are often concentrated in less physically demanding sectors; for example, 30% of taxi and bus drivers are now over the age of 65. For countries undergoing rapid demographic change, Japan offers valuable lessons in increasing female labour force participation and retaining older workers.

- According to the UN classification, a population is considered 'old’ when the share of people aged 65 and over ranges between 14% and 21%. When this share exceeds 21%, the population is described as 'hyper-aged’.

- The demographic ageing index increases as a society grows older. A key threshold indicating the onset of actual demographic ageing is when the population aged 65 and over surpasses the number of children aged 0–14.

- The average age at which individuals aged 49 and over exit the labour market.

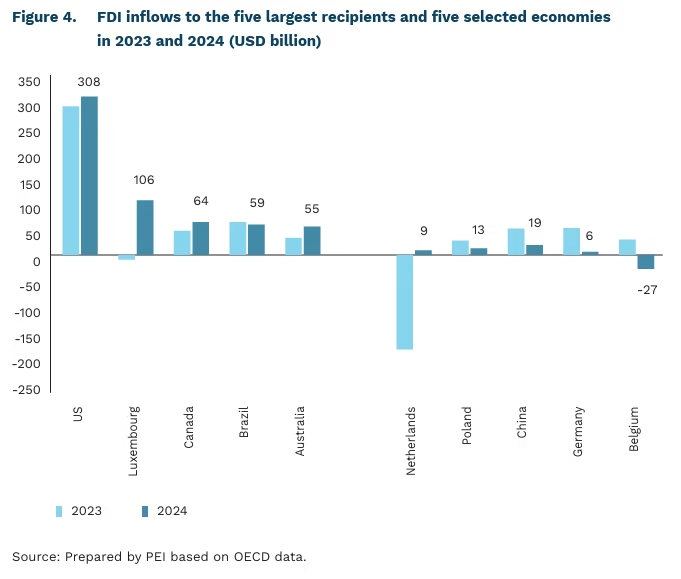

Declines in Foreign Direct Investment in Half of OECD Countries

USD 1.48 trillion total global FDI flows in 2024 (a 1% increase compared to 2023)

-9% estimated change in global FDI f lows when excluding the two largest European investment hubs, Luxembourg and the Netherlands

USD 12 billion value of FDI transactions in Poland in 2024 (a 55% decline)

vious year, according to a new OECD report. However, this figure is somewhat misleading as it masks sharp divergences in FDI performance across individual countries. Without the sharp increases recorded in Luxembourg (USD 115 billion) and the Netherlands (USD 193 billion), global FDI flows would have declined by 9%. The overall slowdown in investment can be attributed to rising geopolitical tensions, increased business uncertainty and divergent interest rate levels globally.

Half of OECD countries experienced a decline in FDI, primarily in Europe but also across most emerging economies. Within the European Union, FDI inflows nearly doubled in 2024, reaching USD 294 billion. However, excluding the increases observed in Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and several other countries, inflows fell by 24%. The United States remained the largest recipient of FDI, attracting USD 308 billion, although it simultaneously reduced its foreign investment outflows from USD 394 billion to USD 299 billion. This shift was largely driven by loan repayments to U.S. parent companies and high levels of reinvested earnings. Luxembourg ranked second with USD 106 billion in FDI inflows, followed by Canada with USD 64 billion, fuelled primarily by mergers and acquisitions.

The decline in FDI inflows to the EU was largely driven by the repayment of intra-company loans. For example, subsidiaries in Ireland repaid loans to their parent entities amounting to USD 88 billion, in Germany USD 36 billion, in France USD 11 billion, and in Poland USD 6 billion. A second key factor behind the decline was net outflows resulting from the resale of previously acquired or established shares. This trend was most pronounced in the Netherlands (–USD 77 billion), Belgium (–USD 10 billion), Hungary (–USD 4 billion), Estonia (–USD 3 billion), and Spain (–USD 0.5 billion).

In Poland, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows fell by 55% in 2024, totalling nearly USD 13 billion—the lowest level since 2017. This figure covers all types of transactions. Equity acquisitions and similar investments declined by USD 7 billion, reinvested earnings dropped by USD 4 billion, and outflows related to debt instruments increased by USD 3 billion.

China recorded a decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) for the third consecutive year, with inflows falling from USD 51 billion to USD 19 billion—the lowest level in thirty years and below those of India and Indonesia. Although capital transactions have been gradually decreasing since 2021, the sharp drop in 2024 is primarily due to reduced reinvestment of profits and exceptionally large loan repayments by subsidiaries to their foreign parent companies. These repayments are estimated at over USD 54 billion, largely driven by the interest rate differential between China and the United States. Despite rising geopolitical tensions and the threat of a trade war, China remains an important, though significantly diminished, destination for foreign investment.

Dominik Kopiński

AI Development Should Complement, Not Replace, Human Labour

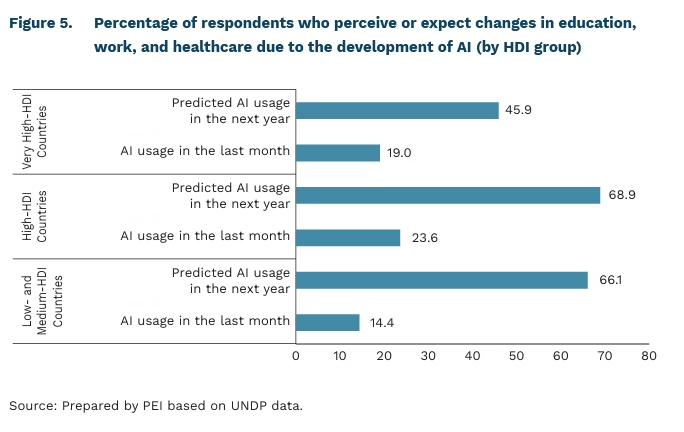

66.1% of respondents in low and medium HDI countries expect AI to be used in the next year

68.9% of respondents in high-HDI countries expect AI to be used in the next year

65.9% of respondents in very high-HDI countries expect AI to be used in the next year

The global growth rate of the Human Development Index (HDI) is slowing, and for the first time in decades, the gap between countries with high and low HDI is widening, according to a new UNDP report. Pre-pandemic projections suggested that the world could reach a high HDI level by 2030. However, updated trends for 2021–2024 indicate that this goal is now out of reach. The UNDP’s 2025 report highlights artificial intelligence (AI) in this context, stressing that the impact of AI on future socio-economic development will largely depend on how societies choose to harness it to shape their development models.

One of the key challenges highlighted in the UNDP report is the need to build a ‘complementary economy’ in which AI enhances rather than replaces human labour. Across countries with low, medium, and high HDI, around two-thirds of people expect AI to be used in education, work, or healthcare. In regions facing shortages of highly skilled workers, AI can act as a tool that enables employees to carry out tasks with greater added value. However, realising this potential requires policies that promote the use of AI to boost productivity— such as introducing safeguards to protect workers at risk of being displaced by algorithms.

The second pillar involves supporting innovation with a social purpose — guiding AI development to align commercial objectives with social values. This requires expanding existing technical standards by introducing new criteria to assess AI’s actual contribution to improving quality of life. For example, it is essential that human agency — defined as individuals’ ability to shape their own lives — remains central to the design of AI systems. The UNDP recommends building systems that learn and evolve through interaction with humans. Open access to source code is seen as a key enabler of this vision.

Another essential component of inclusive AI development is investment in human capital. This requires reforming the education system to place greater emphasis on critical thinking, creativity and interpersonal skills. The focus should shift from rote learning to cultivating adaptable and reflective learners. AI can support this process by enabling personalised learning paths, but it must be viewed as a complementary tool, and not a replacement for teachers.

Krystian Łukasik

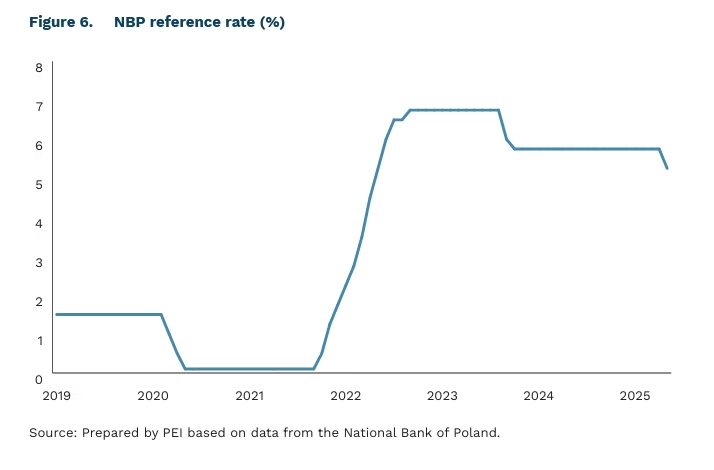

Interest Rates Are Falling in Poland and Globally

5.25% current NBP reference rate

The beginning of May marked Poland’s first interest rate cut since October 2023. The National Bank of Poland (NBP) lowered its reference rate by 50 basis points to 5.25%. According to the Monetary Policy Council (MPC), the move was prompted by a faster-than-expected decline in inflation compared to the March projection. However, MPC members have signalled that no further cut is expected at the June meeting. The next easing of monetary policy is expected in July at the earliest, along with the publication of the latest projection, and will most likely be a reduction of 25 basis points. If current trends continue, a broader debate on policy easing will return in the autumn, when inflation, according to the latest NBP forecasts, will return to its target (2.5% with a possible deviation of 1 p.p.).

Uncertainty surrounding the Federal Reserve’s decision is hindering global monetary easing. On Monday, a breakthrough in trade negotiations between the US and China was announced. The United States reduced tariffs on Chinese goods to 30%, while China lowered tariffs on American goods to 10%. However, the details of the agreement remain unclear, contributing to elevated risk, which is the main reason why the Federal Reserve has opted to maintain interest rates. The Fed left its key rate unchanged at 4.25–4.5%, despite repeated calls from Donald Trump to cut rates. The US central bank operates under a dual mandate: to maintain price stability and maximise employment. The supply shock triggered by the tariffs could fuel both inflation and unemployment, complicating the Fed’s policy response.

Monetary policy easing is also evident in several European countries. In addition to the Polish central bank, the Czech National Bank cut interest rates by 25 basis points, citing falling commodity prices and weaker global economic growth forecasts, which are easing inflationary pressures. The European Central Bank also followed suit, lowering rates for the seventh consecutive time by 25 basis points, attributing the decision to the ongoing disinflation process. As in Poland, the eurozone is experiencing a decline in service price inflation and a gradual slowdown in wage growth.

Piotr Kamiński