Pandenomics 1.0 A fiscal and monetary policy toolbox in days of crisis

Press release

Published: 16/04/2020

The coronavirus pandemic has led to restrictions on the activity of 3 billion people worldwide. The International Labour Organization estimates that up to 25 million people globally may lose their jobs. Consumption is expected to fall by 33%, and each month of economic hibernation has a negative impact on global GDP of 2 percentage points. Massive stimulus packages will shield the global economy from complete catastrophe, but they will certainly not preserve its existing structure. Analysts at the Polish Economic Institute (PIE), in the report “Pandenomics. A set of fiscal and monetary tools in times of crisis”, summarize the first stage of the global fight against the pandemic and propose 10 recommendations to ensure growth during the recovery phase.

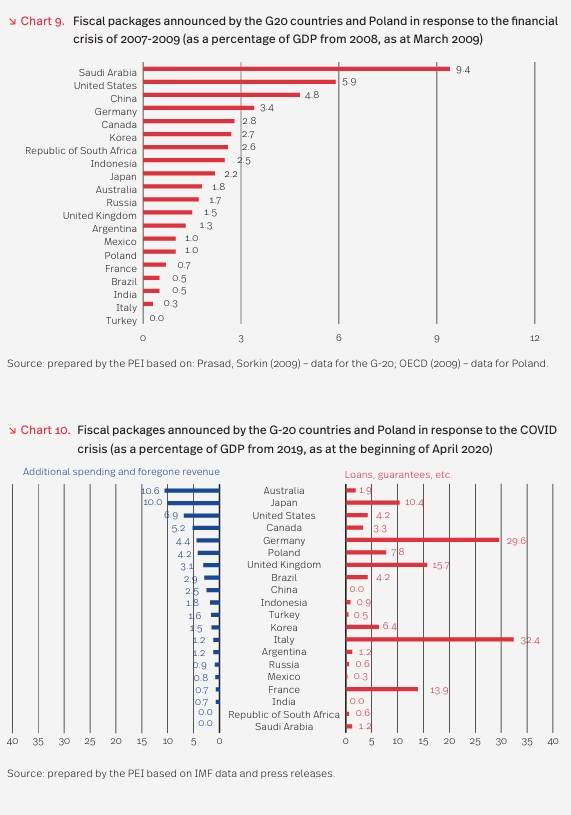

The economic crisis caused by efforts to combat the effects of the coronavirus pandemic is unprecedented in recent decades, as reflected in the scale and speed of government responses. Altogether, G20 countries and Poland have planned to allocate more than USD 4 trillion to fiscal stimulus already in the first phase of the crisis. Poland’s fiscal package amounts to 6.2% of GDP, which is more than 5 percentage points higher than during the 2009 financial crisis. Such a scale of intervention is unsurprising. The current situation appears more serious than the crisis a decade ago, because the degree of restriction on economic activity resembles wartime conditions, says Piotr Arak, Director of the Polish Economic Institute.

Coronavirus as a double shock

The coronavirus pandemic has surprised not only with the speed of its spread across countries and continents, but also with the fact that in the modern world the only effective methods of preventing further spread of COVID-19 have been social isolation and the suspension of activity, including economic activity. The crisis involves a reduction in labor supply due to illness, quarantine, and restrictions, as well as shortages of production inputs caused by disrupted supply chains. These phenomena are accompanied by declines in consumption and private investment, as well as a sharp downturn in sectors most vulnerable to economic hibernation, such as tourism and transport. Access to credit for firms is decreasing, and the stability of the financial sector is weakening. The final transmission channel of the coronavirus shock is social sentiment, characterized by capital outflows driven by investor panic and declining business confidence. A look at data from the United States clearly shows that the current crisis will affect the real economy more severely than the financial crisis over a decade ago. At that time, 8.7 million jobs disappeared from the US labor market. Between 14 March and 3 April 2020, as many as 16.6 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits—and this is only the beginning.

Unprecedented measures for an unprecedented crisis

Comparing the scale of current stimulus programmes (as a percentage of GDP) with those of 2009 shows that far more resources are being devoted today to protecting economies. For example, the USD 2 trillion US stimulus package is more than twice the size of the funds allocated during the 2007–2009 financial crisis. If guarantee mechanisms are also taken into account, the scale of support becomes even larger (e.g. 13.5% of GDP in Poland instead of 6.2%, and 25% of GDP in Germany instead of 4.9%).

Crisis-response economic policies share many common features but differ in emphasis and detailed solutions. Germany applies the Kurzarbeitergeld scheme, aimed at maintaining employment despite falling company revenues, through state support for wage payments when firms lack orders. March reforms expanded the scheme to temporary workers, suspended social security contributions for employees, and increased the number of eligible firms. Similar approaches are used in Denmark, where the government covers 75% of wages, and in the United Kingdom, which covers 80%, as well as in most European countries. France has focused on preserving as many firms as possible through government-guaranteed loans issued by commercial banks, with maximum loan amounts equal to three months of turnover or two years of payroll costs. In Norway, dismissals are relatively easy, but the state offers high unemployment benefits, exceeding 50% of previous wages, payable for 26 weeks within an 18-month period. Spain introduced a ban on dismissals during the crisis; employers are required to pay only social contributions, while employees may apply for benefits of up to 70% of their original salary.

Countries are doing everything possible to protect their economies from a prolonged recession. The European Commission has also taken a number of actions, including allocating EUR 3 billion to the Emergency Support Instrument, EUR 100 billion in loans for countries financing employment protection schemes, and an additional EUR 1 billion in EU budget guarantees for the European Investment Fund. The European Investment Bank, in cooperation with the Commission, proposed EUR 40 billion in loan guarantees and additional liquidity for banks. Temporary deviations from the Stability and Growth Pact were also allowed, enabling budget deficits to exceed 3% of GDP. The European Central Bank committed to allocating EUR 870 billion for asset purchases, including government bonds, by the end of 2020, emphasizes Ignacy Święcicki, Head of the Digital Economy Team at the Polish Economic Institute.

Recommendations

According to the PIE report, crisis phases can be divided into five stages: disruption of production chains, introduction of initial restrictions, full lockdown, gradual easing of restrictions, and the “new normal.” Policy measures should be tailored to the phase in which an economy currently finds itself—hence the dominance of radical actions today. PIE analysts stress that it is already necessary to think about the future. Priority should be given to a new approach to strategic reserves and strengthening the industrial potential of Poland. Countries with strong industrial corporations were able to quickly redirect production to meet medical sector needs when supplies from India and China ceased.

A significant improvement in public services, especially healthcare, is essential—through better organization, staffing, and equipment. Another recommendation concerns leveraging opportunities arising from a new opening in international trade. Maintaining firms’ financial liquidity should also serve the goal of enabling Central Europe to play a larger role in the global economy. An important element of the recommendation package is the creation of a Public Investment Fund, which would finance investment and anti-crisis measures. These would include large infrastructure projects, the energy transition, technological modernization of schools and hospitals, strengthening domestic capacities in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, and increased funding for private-sector R&D, says Paweł Śliwowski, Head of the Strategy Team at the Polish Economic Institute.

Achieving these objectives will require maintaining fiscal stimulus even under conditions of the new normal, meaning that fiscal consolidation will have to wait. PIE analysts also call for the most ambitious possible EU budget, enabling adequate funding for cohesion policy, the Common Agricultural Policy, and climate transformation.

***

The Polish Economic Institute is a public economic think tank with a history dating back to 1928. Its main research areas include foreign trade, macroeconomics, energy, and the digital economy, as well as strategic analyses of key areas of social and public life in Poland. The Institute prepares analyses and expert studies supporting the implementation of the Strategy for Responsible Development and promotes Polish research in economic and social sciences domestically and internationally.

Media contact:

Andrzej Kubisiak

Head of the Communication Team

E-mail: andrzej.kubisiak@pie.net.pl

Tel.: +48 512 176 030