30 years of the Maastricht Treaty

Published: 07/02/2022

Development convergence is taking place in the European Union, mainly due to the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries’ accession to the EU.

In recent decades, the CEECs have developed on average three times faster than the rich economies in the West. However, the differences in terms of development within the EU-15 are higher than before European integration and still deepening, mostly owing to deterioration in the Southern countries’ situation. Compared to 1995, there has been a 20 per cent increase in differences in GDP per capita level in the EU-15. Moreover, the structural differences between EU Member States are almost as large today as they were in 1995, as follows from the report ‘An EU of convergence or divisions? The European economy 30 years after the Treaty of Maastricht’ by the Polish Economic Institute.

‘Generally speaking, we observe a dynamic economic convergence within the EU. However, the blurring of differences in the level of development between countries mainly results from rapid growth in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). In 1995–2020, the CEE countries grew at a rate of 3.1 per cent per year, more than three times faster than the EU Centre. The most impressive growth occurred in the Baltic States. In 1995, GDP per capita in Lithuania was 27 per cent of that in Germany. By 2020, the figure had increased to 72 per cent. In Poland and Romania, GDP per capita increased from 33 per cent and 31 per cent of Germany’s 1995 level to 63 per cent and 56 per cent, respectively, a quarter of a century later. As a result, the standard of living in the CEE countries is rapidly approaching that in Western Europe. At the same time, the EU-15 economies are not converging. A turning point in the ‘old’ Member States’ recent history was the financial crisis of 2008, when the countries of Southern Europe fell into a prolonged recession and the differences between them and Western Europe increased significantly. This is the opposite of the desired outcome – for less wealthy countries to catch up with their richer neighbours, they need to grow more rapidly’, says Jakub Sawulski, head of the macroeconomics team at the Polish Economic Institute.

A two-speed Europe is not a figure of speech

Although economic convergence has been advancing within the EU over the past 25 years as the gap in GDP per capita between EU countries has decreased by an average of 18 per cent, the process slowed down after the financial crisis. In 1995–2010, differences in development within the EU declined 2.5 times faster than today. The Southern countries suffered the biggest hit. The economic stagnation which emerged in the South of the continent has created a two-speed Europe.

Between 2010 and 2020, GDP per capita in Spain and Italy decreased by a combined total of 2.9 per cent and 8.6 per cent respectively. The average Greek was almost 20 per cent poorer in 2020 than a decade earlier. Only Portugal recorded minimal economic growth of 0.1 per cent per year. At the same time, the economies of Germany and Denmark grew by more than 9 per cent. As a result, the disparity in the level of prosperity between the EU’s South and Centre has been growing dramatically. In 1995, Italy was as wealthy as Germany. Today, it is almost 25 per cent poorer.

Institutional convergence is here

Crucially, the Maastricht Treaty largely contributed to the institutional convergence between the Member States. The EU countries are alike in terms of the quality of the law and the scope of economic freedom. This is especially true for the CEE countries. The region has undergone an institutional revolution. The indices show that the differences between the EU Centre and CEE in the assessment of the law have decreased almost fourfold, while those in the scope of economic freedom have fallen more than sevenfold. The indicators are currently slightly lower than those for the Central and Scandinavian countries.

Structural convergence is wanted

The EU Member States are not becoming more alike in terms of their economic structures. In 1995–2019, the distance between the CEE countries and the EU Centre decreased by a total of 5.8 per cent, which means that the structural gap shrank at an annual rate of just 0.2 per cent.

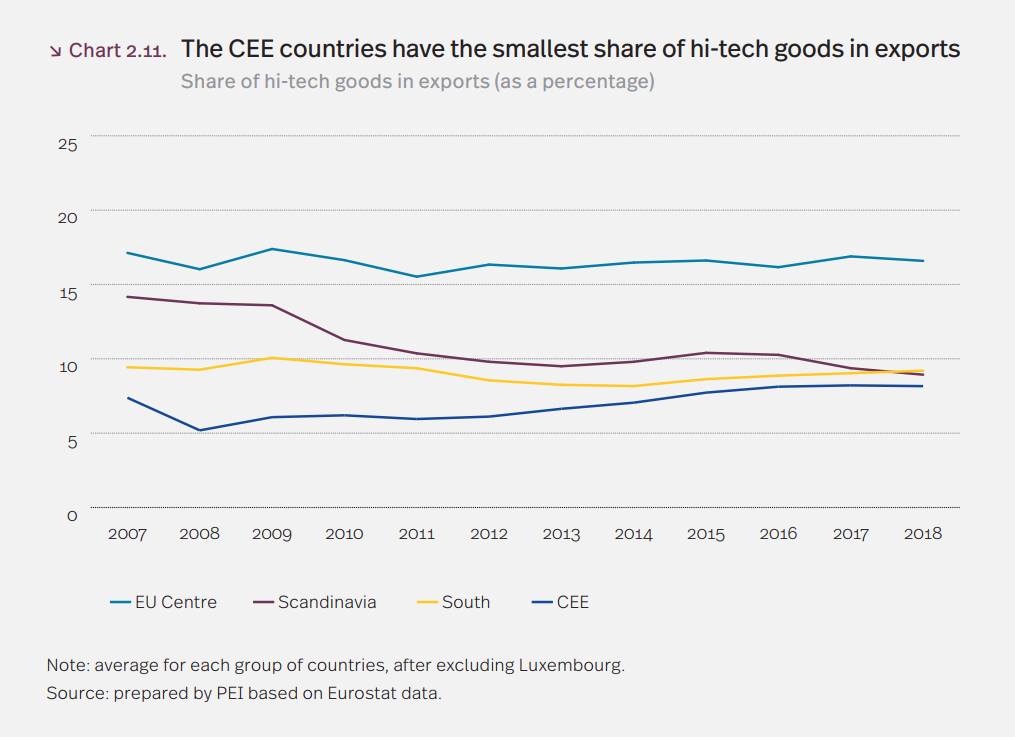

‘Specialisation is progressing in the EU. In recent decades, the South has become mainly a tourist hub. In that region, the tourism contribution to GDP is an average of 6.5 per cent, 2.5 times more than in the EU’s West. At the same time, the CEE countries have expanded industry quite rapidly, but mainly as subcontractors to the West. High-tech exports have been developing almost exclusively in the countries of the EU Centre’, says Krzysztof Marczewski from the macroeconomics team at the Polish Economic Institute.

The convergence of the South was interrupted by the financial crisis in the first place. Structural differences between the economies of the South and the EU Centre had decreased by almost 20 per cent in 1995–2008. However, since the start of the financial crisis, they have systematically worsened, along with the growing gap in the level of development between the countries. The structural distance between the EU’s South and Centre is now as big as it was in 1995 – the past quarter of a century has not led to convergence.

Only the Scandinavian countries have been converging structurally. In 1995–2019, the gap between them and the EU Centre decreased by almost 38 per cent. This rapprochement mainly resulted from the development of the construction industry and the business services sector.

‘The 30 years of the Maastricht Treaty have proven successful with regard to institutional convergence, but not very effective in reducing structural differences. Their persistence could prevent full convergence within the EU. The EU is facing a strategic choice of whether to tighten economic and political integration, implement a fiscal union and boost the mobility of workforce or rather support the economic and technological development in each region of the EU. The latter will require reducing the differences in the balance of payments between the EU Member States’, says Marcin Klucznik, an analyst of the macroeconomics team at the Polish Economic Institute.

***

The Polish Economic Institute is a public economic think tank dating back to 1928. Its research primarily spans macroeconomics, energy and climate, foreign trade, economic foresight, the digital economy and behavioural economics. The Institute provides reports, analyses and recommendations for key areas of the economy and social life in Poland, taking into account the international situation.

Media contact:

Ewa Balicka-Sawiak

Press Spokesperson

T: 48 727 427 918

E: ewa.balicka@pie.net.pl

Kategoria: Makroekonomia / Press releases / Report