Most Poles are in favour of reporting obsolete heating sources to public authorities

Published: 06/10/2020

40 per cent of the Poles assess air quality in Poland to be poor or very poor. At the same time, 2 in 3 respondents are not aware that residential combustion stoves are the main source of air pollution in Poland.

As many as 70 per cent of residents of multi-family buildings disapprove of heating houses with stoves inconsistent with the current technical standards and approve of reporting to the competent authorities air-polluting practices of their neighbours who use non-compliant stoves or fuels, as follows from the report of the Polish Economic Institute entitled ‘Poles and air quality. Social norms as a source of change?’.

The air in Poland ranks among the most polluted in the European Union. The main source of pollutants dangerous to health and the environment, thus to the economy, is non-industrial combustion – the so-called ‘low emissions’, primarily from coal and wood combustion by households.

Further studies extend the catalogue of confirmed adverse effects of deteriorating air quality. The most recent data are particularly alarming as they show a relationship between air pollutants and increased mortality due to the new disease, COVID-19, that has paralysed the world economy in the past months.

Are we prone to take action because of poor air quality?

One air protection priority of the government is the Clean Air (Czyste Powietrze) programme launched in 2018. The programme aims at improving the energy efficiency of over 4 million detached houses by 2029.

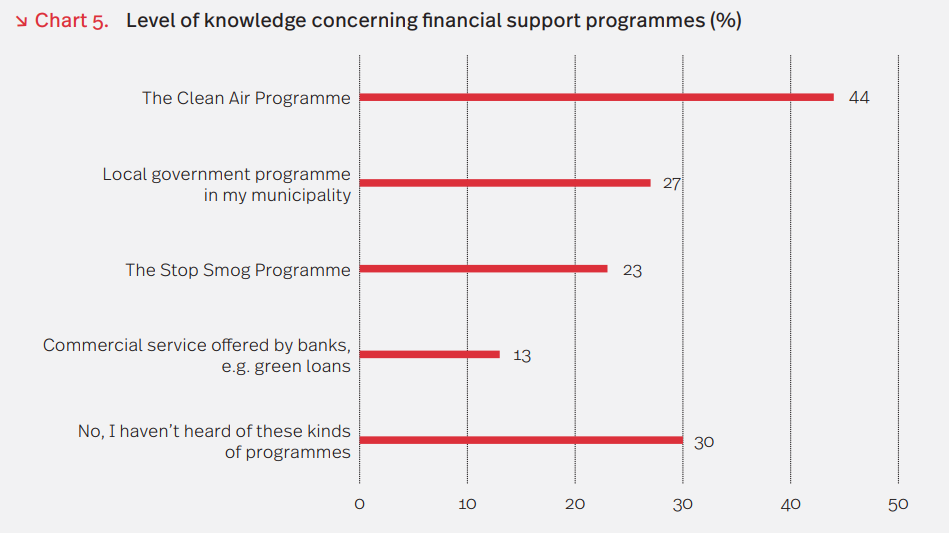

More than ¾ of the Poles are aware of the possibility to obtain an allowance or a loan for funding the replacement of an old stove. But the knowledge of specific financial support programmes is partial. 44 per cent of all the Poles and only 50 per cent of persons living in detached houses have heard of the Clean Air programme. The Stop Smog programme is even less popular. Additionally, it is more frequently known by residents of blocks of flats, i.e. a non-target group.

‘Half of the Poles believe that air quality in Poland has deteriorated in the past two years. 1/3 have noticed more pollutants in their environment. Nearly 2/3 of the Poles take into consideration the effects of air pollution on their and their family members’ health. Many check information on air quality in the neighbourhood,’ says Agnieszka Wincewicz-Price, the head of the behavioural economics team of the Polish Economic Institute.

The measures taken by the Poles faced with deteriorating air quality can be divided into 2 categories. One category includes short-term measures aimed at mitigating the negative impact of breathing harmful air, e.g. surrounding oneself with plants improving air quality (48 per cent) and refraining from opening windows (38 per cent). More than 1/5 intentionally avoid spending time outdoors due to poor air quality. The other category comprises measures with long-term effects, reducing the sources of pollutants. 41 per cent switch over from cars to public transport or bicycles. Definitely fewer people become actively engaged in social campaigns for air protection (24 per cent).

But the scale of major projects reducing low emissions – the main source of pollutants – remains insufficient. Too few Poles decide to replace stoves or boilers harmful to the atmosphere or to implement other energy upgrade measures.

‘One reason is that environmentally-friendly behaviour is shaped by a number of individual factors, e.g. knowledge, awareness, values and social conditions such as the accessibility of necessary infrastructure or the housing situation. Therefore, traditional public policy tools in the form of orders, bans, incentives and penalties are no guarantee of a successful programme since they frequently neglect significant intangible elements of behaviour and decision-making processes: psychological, social or even moral factors,’ adds Agnieszka Wincewicz-Price.

Social norms may be the key to success

No major improvement of air quality in Poland can be achieved solely by applying financial incentives and regulations laying down the permissibility of specific heating equipment and fuels. It is also necessary to make owners of obsolete boilers – the target recipients of financial assistance – aware of their direct influence on air quality and social expectations associated with air pollution. It can be achieved with the use of behavioural tools relating to social and moral norms.

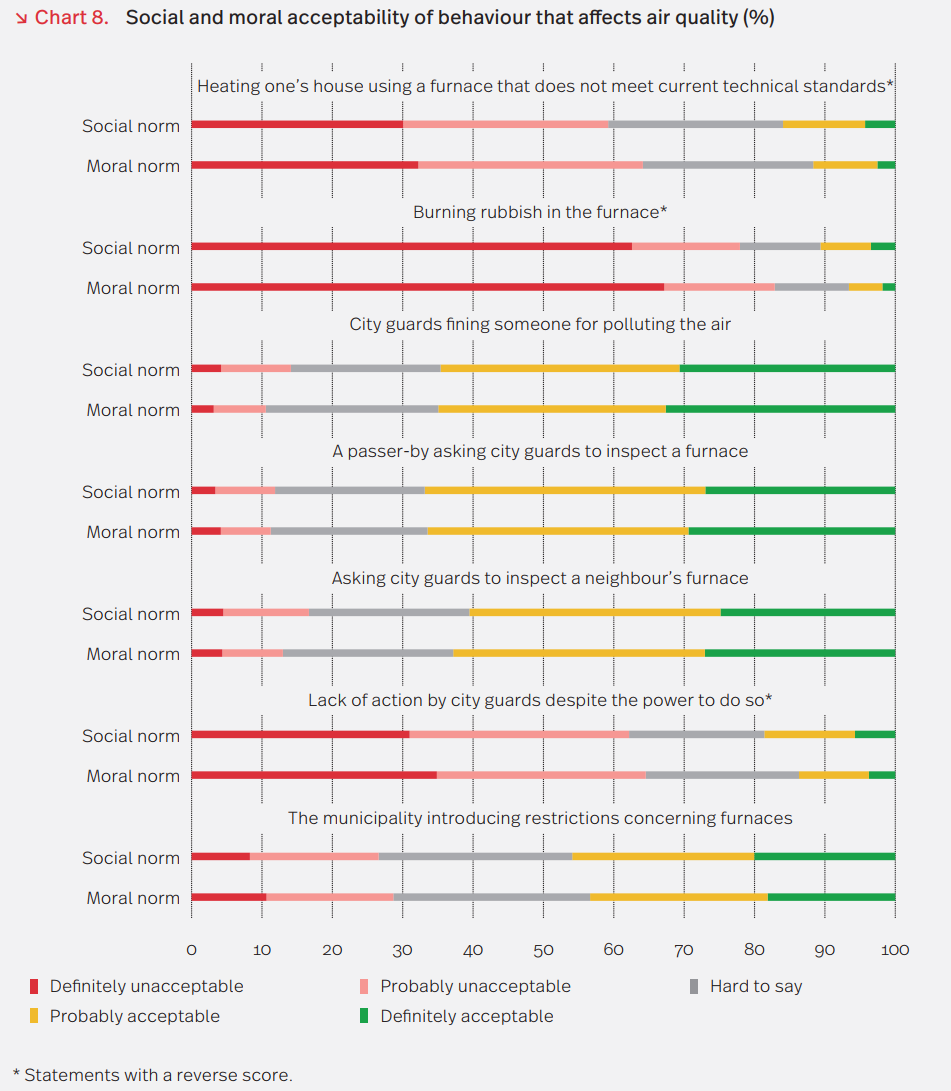

In the survey of the Poles conducted by the PEI, the respondents were asked to indicate their attitudes to several situations describing behaviours conducive to air protection or harmful to air quality. Half of those surveyed evaluated the behaviours in terms of moral norms, i.e. at the level of their individual affirmation or negation of a behaviour or an attitude. The other half made their assessments from the point of view of social expectations approving or disapproving of a behaviour or an attitude.

The respondents were particularly critical of the practice of burning unauthorised materials in domestic stoves. In that case, more Poles personally disapprove of such a behaviour (over 80 per cent), whereas slightly fewer expect a similar general public opinion (78 per cent).

Somewhat more people approve of using stoves or boilers inconsistent with the applicable standards. However, the practice is disapproved of by 64 per cent of the Poles, whereas 59 per cent consider it to be socially unacceptable.

More than 60 per cent of the Poles are in favour of reporting such conduct to the competent authorities. Similarly favourable opinions were expressed with regard to imposing fines on house owners using unauthorised stoves or boilers (65 per cent of positive assessments from both moral and social perspectives).

How do we use behavioural knowledge to improve air quality?

As demonstrated by the survey conducted by the PEI, most Poles have firm and coherent views on the normative assessment of behaviours that influence air pollution and protection. Moreover, individual assessments are largely consistent with the evaluation of social expectations concerning such conduct. Nevertheless, the measures taken by the Poles remain insufficient.

In the report, the PEI analysts recommend two lines of action. One should target owners of detached houses still using obsolete stoves or boilers. It is necessary to better recognise their situation by taking account of specific local conditions and simplifying the related procedures. It is also important to shape citizenship for the effect of social pressure to disapprove of using low-quality fuels and obsolete stoves and to treat such behaviours as socially detrimental.

The other line of action is related to the system of controlling the Poles’ compliance with the legislation in force regarding residential combustion stoves. It is worth supporting the social capital identified in the survey (especially the acceptance of reporting irregularities to the municipal police) with appropriate incentives and infrastructure.

It can be achieved by clearly communicating to the residents of particular municipalities the possibility to report abuse by telephoning the relevant numbers of the local municipal police. It is worth considering the provision of a separate number for submitting such reports. It follows from our survey that such numbers have only been made available in 32 out of the 232 municipalities surveyed. The survey findings suggest that informing the residents of the possibility to submit such reports and of their social acceptability may activate the local communities and thus minimise detrimental behaviours of owners of obsolete boilers as well as increasing the number of inspections where they are advisable.

An important component of the infrastructure supporting preventive measures of the municipal police would be to equip such units with appropriate devices allowing accurate and up-to-date measurements of local pollutants and to communicate such data to the local communities. Some municipalities use drones and special smog measurement vehicles. But our survey shows that few municipalities have implemented such measures (drones – 10 per cent, smog measurement vehicles – below 4 per cent).

The Polish Economic Institute is a public economic think-tank dating back to 1928. Its research spans trade, macroeconomics, energy and the digital economy, with strategic analysis on key areas of social and public life in Poland. The Institute provides analysis and expertise for the implementation of the Strategy for Responsible Development and helps popularise Polish economic and social research in the country and abroad.

Media contact:

Agata Kołodziej

Head of the Communications Team

tel. 48 727 427 918

Kategoria: Climate and Energy / Press releases / Report / Reports 2020