The investment in the EU enlargement has paid off and boosted growth, but the Community is faced with stagnation

Published: 23/09/2020

According to the new secular stagnation theory, the ongoing technological changes and unfavourable demographic trends reduce demand for capital and labour.

The hypothesis is put forward on a par with climate change warnings, having given rise to the environmental movement referred to as post-growth. Piotr Arak, the Director of the Polish Economic Institute, discussed the benefits of European integration as well as the related costs and challenges in this year’s Professor Bronisław Geremek lecture entitled ‘Costs and benefits from European integration in the post-COVID world’.

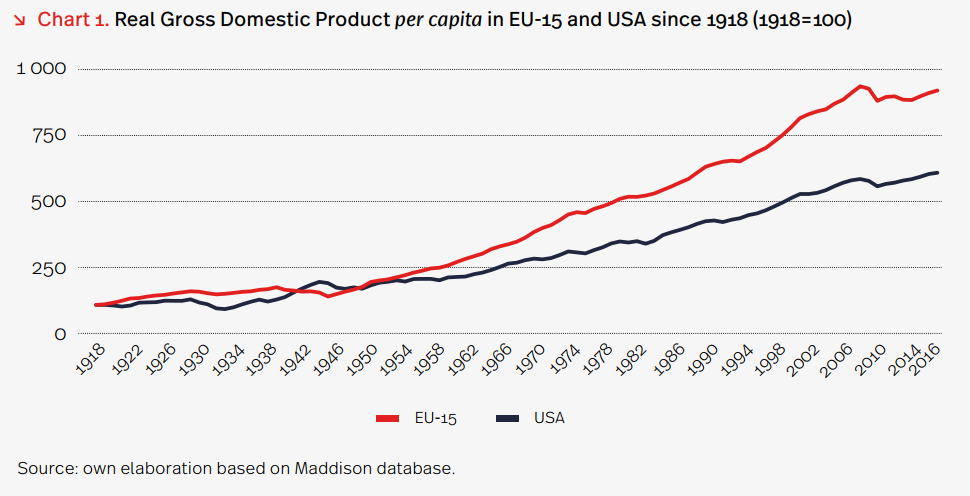

‘There are many indications that we live in times of new secular stagnation. It is reflected in the existing demand barriers, economic slow-down, a rising difference between the potential and actual GDP growth and permanent unemployment. The EU-15 have noted lower economic growth rates than the new Member States that have caught up with their predecessors due to factors such as the common market and investment inflows. In the latter group, the EU accession was followed by an increase in GDP and average wages. Since 2004, GDP per capita has risen by more than 60 per cent in Lithuania, Romania or Poland, whereas it has dropped in Italy and Greece,’ says Piotr Arak, the Director of the Polish Economic Institute.

In this context, the Member States are frequently and falsely divided into givers and takers, a division that neglects the economic effects of redistribution on consumption or trade. The 2004 enlargement of the European Union involved a major injection of funds for the EU-15, with Luxembourg and Austria gaining the most (EUR 6,600 per capita and EUR 1,820 per capita respectively). The least benefits were derived by Portugal (EUR 51.70 per capita), Spain (EUR 174.70) and France (EUR 260.90). With regard to direct contributions, 8 out of the 15 countries were net payers, but in terms of economic gains of the EU enlargement, each Member State proved to be a winner. The related gains can be identified by calculating the benefits generated per euro invested. Taking that criterion into account, we will see Germany (EUR 13.60 per capita), the United Kingdom (EUR 11.20) and Austria (EUR 10.50) as the largest beneficiaries.

Apart from obvious benefits, the EU-13 have also incurred certain hidden costs. Those are related to issues such as emigration, a pressing problem for the Central and Eastern European countries. It was unexpected that the population outflow from the region should reach the levels observed in 2004: an average of 4.78 per cent of the EU-13’s citizens moved to the EU-15, with the largest migrations noted from Romania (ca. 10 per cent), Croatia (8 per cent) and Lithuania (6 per cent). The tax havens pose another problem, generating billions of losses every year. According to estimates, since 2004, they have cost Poland EUR 9 billion, the Czech Republic – almost EUR 5 billion, whereas Hungary – more than EUR 3.5 billion.

Challenges for the future

The current problem faced by the whole world is the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; in contrast to the financial crisis of 2008–2009, it was first reflected in the market presence of businesses and job losses. Although it is difficult to predict the future course of the pandemic, most economists expect a marked bounce-back in 2021.

Europe’s stagnation is the most serious threat. Considering the previous GDP patterns, an enormous threat facing us is that Europe may stop growing. In terms of investment as a share of GDP (21.3 per cent in Europe), we are behind China (43.3 per cent), Korea and India (ca. 31 per cent each), or even Russia (22.8 per cent). In order to improve Europe’s post-pandemic situation, in June 2020, the leaders of all the Member States adopted a financial plan estimated at nearly EUR 2 trillion. Its largest direct beneficiaries will be Italy (EUR 150.2 billion), Spain (EUR 142.6 billion) and Poland (EUR 124.9 billion).

‘The pandemic has demonstrated that we must be much better prepared for the unexpected. As predicted by experts of the World Economic Forum, extreme weather conditions, unsuccessful climate action, natural disasters, the loss of biodiversity and human-made environmentally mediated diseases would pose the most significant risks to the world. Infectious diseases were last identified as a major threat in 2015 when the Ebola epidemic broke out. The current pandemic has only more explicitly shown that we must be prepared for the unpredictable,’ concludes Piotr Arak.

The Polish Economic Institute is a public economic think-tank dating back to 1928. Its research spans trade, macroeconomics, energy and the digital economy, with strategic analysis on key areas of social and public life in Poland. The Institute provides analysis and expertise for the implementation of the Strategy for Responsible Development and helps popularise Polish economic and social research in the country and abroad.

Media contact:

Agata Kołodziej

Head of the Communications Team

tel. 48 727 427 918

Kategoria: Other / Press releases / Report / Reports 2020