Economic Weekly 52/2025, December 31, 2025

Published: 31/12/2025

Table of contents

Inflation Fight Ends in 2025 as Economic Activity Picks Up

1.75 pp total interest rate cuts by the Monetary Policy Council (MPC) in 2025

1.6% momentum of core inflation (SAAR 3M) in November 2025

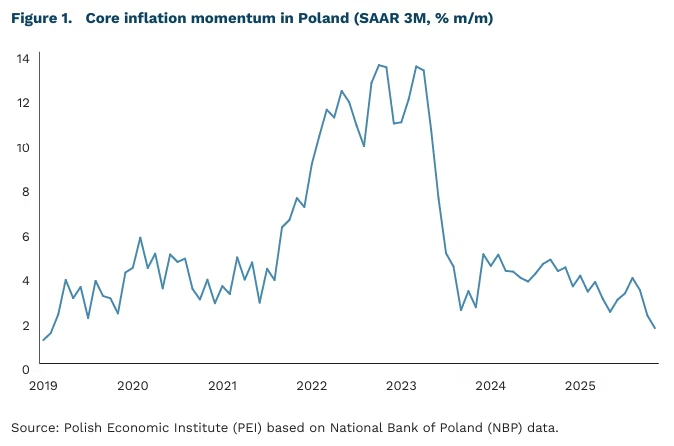

The past year in the Polish economy was marked by a transition from fighting inflation to a phase of cautious stabilisation. The Monetary Policy Council (MPC) cut interest rates six times, by a total of 175 basis points. These decisions were made possible primarily by a clear easing of inflationary pressures, reflected in the decline in year-on-year CPI inflation from 4.9% in January to 2.5% in November, as well as by improved inflation outlooks in forecasts. In recent months, CPI inflation has consistently surprised on the downside, coming in below market consensus. Core inflation, excluding food and energy prices, also fell year on year to 2.7% in November, while its momentum (SAAR 3M(1)) dropped to 1.6%, falling below 2% for the first time since February 2019. It should be noted, however, that the full impact of the current interest rate cuts on price dynamics will materialise with a significant lag, estimated at around 8-9 quarters.

Despite still relatively tight monetary policy, economic activity gradually began to accelerate, supported by the disinflation process, sustained positive real wage growth, and increasing inflows of EU funds. GDP growth in 2025 is estimated at around 3.5-3.6%, with the recovery encompassing both services and industry, while construction has begun to gradually emerge from stagnation. Real-economy outcomes in the second half of the year were positive, with particularly strong investment growth, which accelerated to 7.1% y/y in the third quarter. For the first time in over a year, net exports also made a positive contribution to GDP growth, despite faster import growth.

As domestic conditions improve, developments in the global economy are also gaining importance and may further support economic activity in Poland in the coming quarters. Improving global prospects, particularly the gradual recovery and rebound in demand in the euro area, should bolster external demand for Polish goods and services. The scale of the recovery in the euro area in 2025 turned out to be stronger than previously forecast, with GDP growth estimated at around 1.2%, though remaining geographically uneven. The US economy also recorded strong results in the first half of the year, partly due to inventory accumulation ahead of the introduction of tariffs. Full data for the second half of the year will be available with a delay due to the government shutdown. The magnitude and direction of the impact on the Polish economy will nonetheless depend on geopolitical developments, the pace of implementation of Germany’s fiscal package, and the shape of US trade policy.

- SAAR 3M momentum illustrates the annual inflation rate that would prevail if the pace of price growth observed over the past three months were maintained for an entire year.

Piotr Kamiński

Partial Consolidation of Funding for Industrial Innovation in the New EU Multiannual Budget

EUR 1.98 trillion EU long-term budget for 2028-2034

EUR 451 billion planned expenditure on competitiveness and research

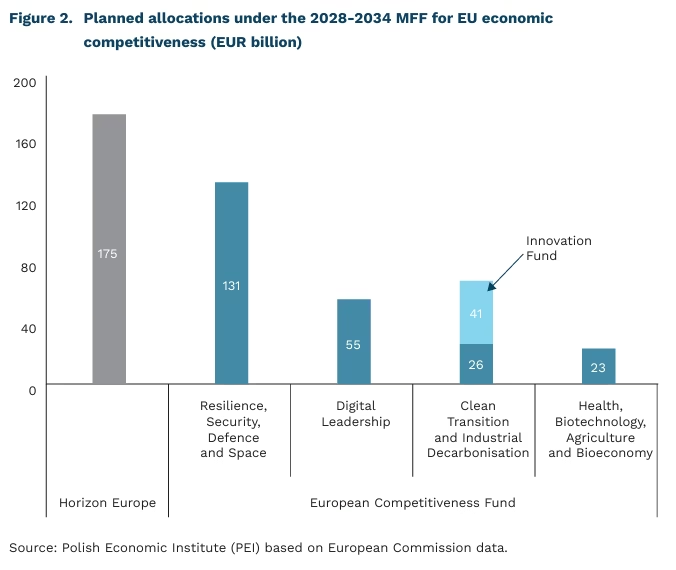

The current EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) expires in 2027, and negotiations on the new MFF for 2028-2034 are under way. The total value of the new MFF proposed by the European Commission amounts to nearly EUR 2 trillion (EUR 1.98 trillion at current prices), corresponding on average to 1.26% of EU gross national income in 2028-2034 and representing the highest nominal level of spending in the history of the Union. The new MFF envisages greater flexibility of budgetary instruments to enable faster responses to unforeseen circumstances and new policy priorities. It also provides for simplified financing mechanisms, improved access to funds, and greater effectiveness of spending (European Commission, 2025). In the proposal, the budget structure is based on four pillars: (1) the European social model and quality of life, (2) competitiveness, prosperity and security, (3) Global Europe, and (4) administration.

From the perspective of strengthening EU economic competitiveness, significant importance is attached to the development of the clean-tech industry. This sector encompasses a broad range of technologies and industrial solutions aimed at reducing emissions and improving energy efficiency, including low- and zero-emission processes in energy-intensive sectors and the entire clean-energy value chain, i.e. from generation to final use. The development of the clean-tech industry is treated as a cross-cutting element of the budget, serving three objectives: enhancing EU competitiveness, increasing energy and technological security, and supporting the energy transition under climate policy (European Commission, 2025).

The main, though not the only, instrument for supporting clean industry in the EU is to be the European Competitiveness Fund, designed to concentrate, simplify and accelerate financing for strategic technologies and to mobilise public and private investment in key areas of transformation. The new fund is intended to bring together several existing instruments, including InvestEU, to enable more effective centralised management. Its resources are to support clean transformation and industrial decarbonisation, digital transformation, health and biotechnology, as well as agriculture, the bioeconomy, defence and space. At the same time, support for clean-tech industry will not be limited solely to the European Competitiveness Fund and, similarly to the current financial perspective, will remain dispersed across various instruments and budget headings within the MFF. The absence of full concentration of clean-industry financing within the ECF reflects the sector’s multidimensional nature, spanning cohesion and industrial policy, research and energy, and security. In addition, clean-tech projects may be supported by national funds under state-aid guidelines. Already today, the CISAF framework provides instruments dedicated to industrial decarbonisation and the production of low-emission technologies.

To date, Poland has attracted a lower share of funding from EU central programmes than would be expected given its potential. Under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme for 2014-2020, Poland received EUR 748 million, representing 1.21% of total funding allocated to the EU-28. This was significantly below Poland’s share of EU GDP (including the United Kingdom), which amounted to 3.2% in 2019. At the same time, Poland and the wider Central and Eastern European region recorded success rates around 13%, compared with the EU average of 16%. In the subsequent programme for 2021-2027 (Horizon Europe), Poland increased its share of obtained funding to 1.57%, although this remained almost three times lower than Poland’s share of EU GDP (EU-27), which reached 4.7% in 2024. Poland performed even worse in projects funded by the European Research Council (ERC). In some other, less prestigious funding instruments, Poland’s participation was slightly higher. For example, within the Knowledge and Innovation Communities (EIT KIC) under the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, Poland achieved a 2.36% share, although this corresponded to much smaller absolute amounts (EUR 45 million).

In the Innovation Fund financed from the EU ETS, dedicated to clean technologies and operating outside the MFF, Poland secured EUR 429 million, or 3.3% of total EU funding. Polish beneficiaries are dominated by initiatives with a high share of foreign capital: more than half of the amount went to a subsidiary of the French group Holcim (successor to Lafarge); EUR 91 million to a subsidiary of the Korean battery manufacturer LG Energy Solution; EUR 75 million to a project of the bankrupt Swedish group Northvolt; and EUR 17 million to the Spanish company WINDAR, a co-investor with a Polish entity, for the production of components for offshore wind-turbine towers.

Central funds linked to competitiveness and innovation are set to play a larger role in the new budget. Total allocations for EU economic competitiveness will amount to EUR 451 billion – nearly one quarter of the entire MFF – of which the Competitiveness Fund is to manage EUR 234 billion. Horizon Europe funding will double from EUR 86 billion to EUR 175 billion, but these resources will remain outside the Competitiveness Fund, albeit closely linked to it. A total of EUR 131 billion is to be allocated to funds related to resilience, security and space; EUR 67 billion to clean transport and industrial decarbonisation (including EUR 41 billion under the Innovation Fund, compared with around EUR 15 billion in the current perspective); EUR 55 billion to digital issues; and EUR 23 billion to health, biotechnology and agriculture.

Negotiations on the detailed shape of the MFF will intensify in 2026. Discussions to date indicate that it will be difficult to secure the agreement of countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland, to debt instruments, while the Netherlands and Austria have declared their intention to limit the size of the EU budget. Central European countries are concerned about the planned merger of cohesion policy and the common agricultural policy into a single funding envelope. The need to establish a European Competitiveness Fund does not raise major controversy, although its specific design does. Two key demands from Member States are greater influence over the Commission’s spending decisions and, for some countries including Poland, assurances of geographically balanced allocation of funds. It is worth noting that, following the publication of the MFF proposal by the European Commission in July, the Council’s work so far on the individual elements of the ECF proceeded without major controversy.

Krzysztof Krawiec, Marek Wąsiński

2025 Recorded the Highest Employment Level on Record, While Labour Demand Declined

17.36 million number of people employed in Poland in Q3 2025

94.7 thousand number of job vacancies in Poland in Q3 2025

7.4% share of employees working part-time in Poland in Q3 2025

In 2025, Poland recorded the highest number of people in employment. In the third quarter of the year, according to Statistics Poland (GUS), 17.361 million people were employed. This was the highest level observed to date and 0.5% higher year on year. Previously, employment had exceeded 17.3 million at the end of 2023, when it reached 17.323 million.

Poland’s employment rate remains higher than the EU average. In the third quarter of 2025, the employment rate among people aged 20-64 stood at 79%, which was 3 pp higher than the EU average. Lower employment rates were recorded, among others, in France, Austria, and Finland. The highest employment rates were observed in Malta (84.7%), the Netherlands (83.4%), and Czechia (82.9%).

The number of job vacancies declined in 2025. According to GUS data, 94.7 thousand job vacancies were recorded in Poland in the third quarter of 2025, representing a 17% decrease year on year. In every quarter of 2025 for which data are already available (data for the fourth quarter are not yet published), the number of vacancies was lower than a year earlier. Similarly, the vacancy rate(2) declined quarter on quarter, continuing the downward trend observed since 2021. In the third quarter of 2025, the vacancy rate stood at 0.74%.

The share of part-time employment increased. In 2025, the proportion of part-time workers exceeded 7% for the first time in both the second and third quarters. In nominal terms, 1.3 million people worked part-time between July and September 2025, accounting for 7.4% of all employees, while 16 million people were employed full-time during this period.

In 2025, 47% of people who changed jobs found new employment within two months. According to a survey conducted in July 2025 for pracuj.pl, a further 41% of respondents needed between three and twelve months to find a new employer. The results apply to individuals who had changed jobs within the previous two years at the time of the survey. In cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants (Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław, Łódź, and Poznań), 54% of respondents found a new job within a maximum of two months.

2. Share of job vacancies in total employment in the economy.

Jędrzej Lubasiński

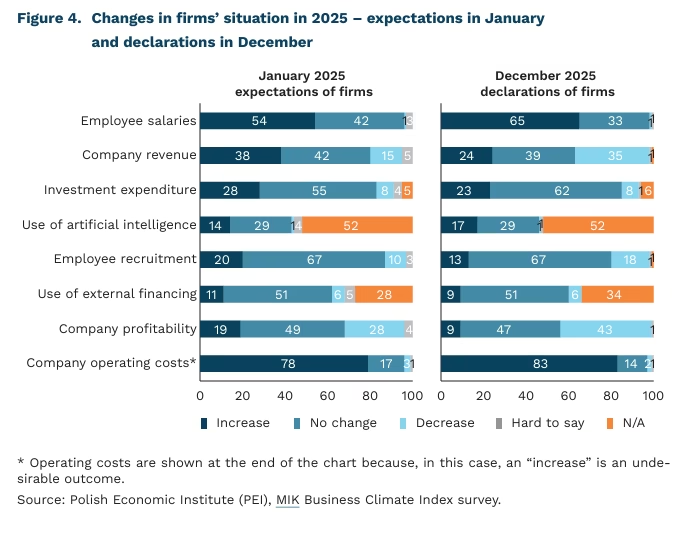

Business Conditions at Year-End Worse Than Expected at the Start of 2025

24% of firms reported an increase in revenues in the past year, compared with 38% that had expected this

83% of companies experienced an increase in operating costs, compared with 78% that had anticipated this

67% of firms reported no change in employment, in line with their expectations

According to a survey by the Polish Economic Institute (PEI), conducted as part of the MIK (Monthly Business Climate Index), companies at the beginning of 2025 expected their situation to be better than it ultimately proved to be in December. Above all, they anticipated higher revenues. While in January 2025 as many as 38% of firms expected an increase in revenues, by December only 24% reported that such growth had actually occurred. At the same time, 35% of enterprises indicated in December that their revenues had declined, whereas at the beginning of the year only 15% had expected a decrease. Although this pattern was observed across firms of all sizes and sectors, only among large enterprises did the year end with a continued predominance of firms reporting revenue growth (32%) over those reporting a decline (20%).

In December, more firms (regardless of size and sector) reported a decline in profitability than had anticipated such a decline at the beginning of the year. While in January 28% of companies feared that their profitability would fall over the course of the year, by December as many as 43% confirmed that such a decline had occurred. Similarly, whereas 19% of firms in January expected an improvement in profitability, only 9% declared an actual increase in December. This outcome is unsurprising given that at the beginning of the year 78% of firms anticipated rising operating costs, while by December 83% reported that such an increase had indeed materialised. More than half of enterprises planned wage increases in January, and by December as many as 65% stated that they had actually raised wages. Combined with the marked decline in profitability, this may, over the longer term, translate into stronger pressure on margins, as firms raised wages despite more challenging market conditions.

The labour market remains relatively stable, but investment growth was slightly weaker than firms had expected. At the beginning of the year, one in five enterprises declared an increase in employment, yet by December only 13% reported that they had actually expanded their workforce (while 18% indicated a reduction). Firms reduced employment more often over the course of the year than they had anticipated at its outset. Nevertheless, by year-end 67% of companies reported neither increasing nor decreasing employment – the same proportion that had expected no change in January. Meanwhile, 28% of firms had anticipated higher investment spending, but by December it turned out that only 23% had increased investment. Investment therefore tended to stabilise rather than accelerate. As a result, instead of the expected expansion, the year was characterised by heightened caution and a focus on maintaining existing levels of activity. Although the December reading of the MIK (Monthly Business Climate Index) shows positive sentiment outweighing negative sentiment for the third consecutive month, firms simultaneously report a growing burden of payment backlogs (43% of responses; an increase of 4 pp month on month). The PMI remained relatively stable towards the end of the year (albeit below the 50-point threshold), but manufacturing firms increasingly reported declining employment, subdued demand, and rising costs.

Katarzyna Zybertowicz

2025 Marked by Debate Over a Speculative Bubble in the AI Sector

19 AI factories planned to be launched in the EU

6.7 estimated ratio of AI investment to revenues

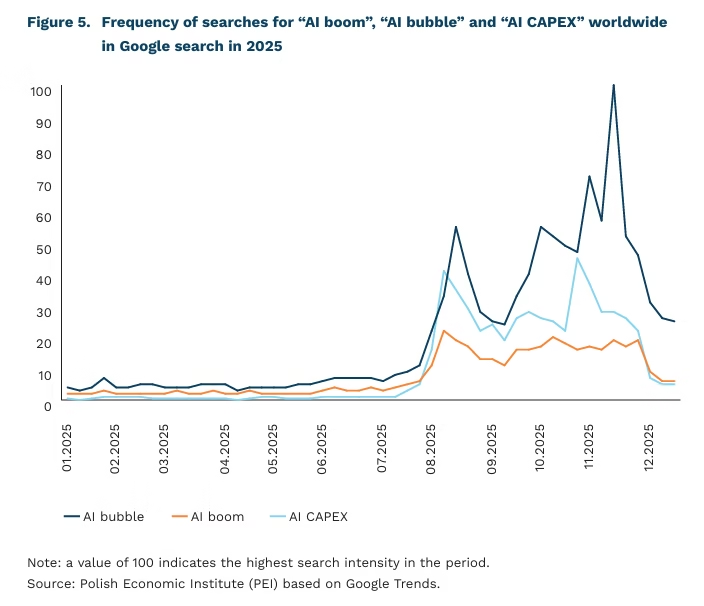

2025 was marked by growing concerns about the formation of a bubble in the AI market, an ongoing race among developers of the most advanced models, and turbulence surrounding AI regulation. Rapidly rising spending on data-centre infrastructure, particularly on graphics processing units (GPUs) used for AI applications, has collided with doubts about the scale of practical use cases and future profitability. In the sphere of European public policy, concerns about the negative effects of technological dependence on the United States and China, combined with an explicit desire to maintain technological leadership, have pushed Europe towards measures aimed at strengthening domestic production and technological sovereignty, while simultaneously contributing to the postponement of some regulatory initiatives.

In August 2025, when Sam Altman mentioned in an interview that an investment bubble was emerging in the AI sector, and MIT published a report indicating that only 5% of f irms generate profits from deploying this technology, interest in the topic surged in the media and online. The debate has often drawn comparisons with the early-2000s dotcom bubble, when investor enthusiasm for the internet led to massive capital inflows into firms offering little more than promises of future profits. However, as discussed in a PEI podcast, the current situation differs in an important respect: investments in infrastructure (CAPEX – the layer on which most bubble discussions focus) are being made by firms with substantial capital buffers, and rising debt does not threaten their fundamentals. Although experts estimate that the ratio of AI investment to revenues stands at around 6.7, suggesting it has crossed a warning threshold, this figure has been declining in recent months, pointing to greater stability. The bubble debate is also reflected in tensions surrounding the race to build ever more powerful models. On the one hand, new models of ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok and the Polish Bielik have been announced; on the other, doubts about the limits of large language models (LLMs) have become increasingly vocal.

The European Union has also joined the infrastructure race, announcing a list of socalled AI factories and plans for gigafactories – facilities intended to provide large-scale computing power for training next-generation AI models. This has sparked a debate over the purpose of these centres. According to some experts, Europe should focus on its strengths by developing specialised models that deliver solutions in specific environments (e.g. industry or healthcare), rather than competing for dominance in general-purpose large models. A broader context is the discussion on technological sovereignty: expanding data-centre capacity may result in strong dependence on a single processor supplier.

Poland lacks firms directly involved in the global AI investment race, but the broader dilemmas outlined above are highly relevant domestically. While 2026 is unlikely to resolve all uncertainties, it will be a crucial year for decisions on how to use the AI factories being developed in Poland, the planned gigafactory, and concrete measures to accelerate the diffusion of advanced digital technologies across the economy. For years, Poland has highlighted its assets: well-educated specialists, data resources and a diversified industrial base. The hope is that in 2026 these strengths will finally translate into tangible benefits.

Ignacy Święcicki

Can Uncertainty Be Good for the Economy?

The transition from the old year to the new is usually a time marked by uncertainty about how the coming months will unfold, what changes they will bring, and whether (and how) it is possible to prepare for them. Uncertainty is typically perceived negatively, not only at the personal level but also in economic and business terms. Entrepreneurs are particularly affected by uncertainty related to changing legal regulations and the broader economic environment. This uncertainty often translates into reduced investment activity and employment, as well as increased savings, by both firms and consumers, which in the longer term leads to a slowdown in economic growth.

At the start of a new year, however, it is worth paying attention to the positive dimension of uncertainty, especially in the context of economic decision-making. In economic theory, particularly within the evolutionary economics tradition, uncertainty is seen as a driver of so-called adaptive behaviour, which increases the efficiency and resilience of firms (as well as individual investors) in the face of change. Although the need to build resilience and enhance adaptive capacity has received increased attention in recent years marked by global crises, the classic theory of decision-making under uncertainty developed by Armen Alchian dates back to 1950. In his seminal article, Alchian challenged the mainstream economic assumption that firms’ decisions are guided by profit maximisation, arguing that decisions are made under conditions of incomplete information and therefore can never be perfectly rational.

Experts point to three areas in which uncertainty may prompt firms to behave more rationally: (1) greater caution in spending on growth and expansion; (2) a stronger focus on core activities, products, markets and competences, rather than risky diversification into less familiar areas; and (3) increased attention to and adjustment to the needs of customers, who themselves are also facing uncertainty.

Research also shows that market uncertainty encourages firms to implement innovative solutions, both in internal management processes and in the products and services they offer. Uncertainty also prompts firms to shift their strategic orientation from long-term profit maximisation towards short-term growth. This phenomenon is referred to as the opportunity expectation effect.

It should be emphasised, however, that a high degree of uncertainty, especially at the institutional level, may negatively affect the adaptive and innovative capacities of individuals and enterprises. This poses a particular challenge for institutions responsible for shaping the economic environment, which should, within their competences and capabilities, ensure predictability and transparency of regulatory changes and stability in the functioning of economic entities, rather than further increasing an already high level of uncertainty.

Agnieszka Wincewicz-Price